Women Intellectuals and Authors of Ancient & Medieval India - V

Total Views | 13

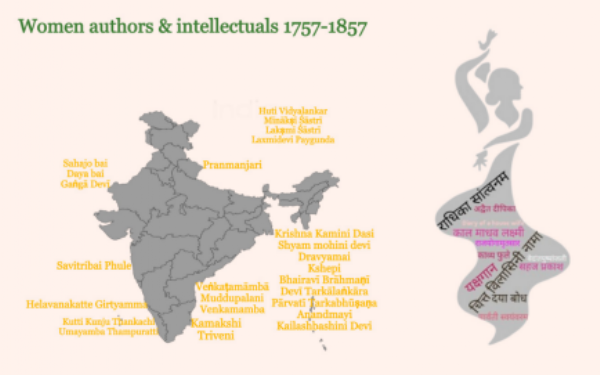

Women Authors & Intellectuals 1757-1857

When Muddupalani wrote 'Radhika Santvanam' in the period around 1760, little did he know that after 200 years, it would attract the attention of another equally talented woman, Bangalore Nagarathnamma (1878-1952), who would find the manuscript to publish it in 1911. It is an irony that the Victorian era mentality of British rulers banned the book for 'erotic content'. To understand the significance of this story, we have to know who were Muddupalani and Bangalore Nagarathnamma were.

The theme of Radhika Santvanam is bold. It is a story of a love triangle between Krishna, Radhika and ila. There are erotic descriptions of relationships, and its women characters are shown taking the initiative passionately. It was not surprising that Muddupalani wasaDevdasi attached to the court of Pratap Singh of Tanjor kingdom. But her literary talent was not limited to one subject can be seen from her other works. She has translated the famous Ashtapadi of Jaydev from Sanskrit to Telugu and Thiruppavai of Saint Andal from Tamil to Telugu. A woman with exceptional talents, she was well versed in Sanskrit, Telugu and Tamil. So was Bangalore Nagarathnamma. An accomplished dancer, singer and violinist, she was proficient in Telugu, Kannada, Sanskrit and English. She was the one who built Tyagraj Samadhi and started the now famous Tyagraj music festival.

Radhika Santvanam seems to have had its ups and downs. The work must have enjoyed a considerable popularity through the nineteenth century, for a Teluguscholaremployed by C. P. Brown (1798 – 1884), Paidipati Venkata Narusu, wrote a commentaryon it. C. P. Brown dedicated his life to Telugu literature and language. He must have considered it important enough to have a commentary written by a scholar. But there was a twist. It was edited to remove some parts considered to be 'erotic'. Perhaps this is what irked Bangalore Nagarathnamma. She found the original manuscript and published the complete version. Ironically enough, a noted social reformer, Kandukuri Veeresaling, filed an obscenity case against Radhika Santwanam, and the book was banned. The ban was removed only after independence. Now with changing times, it isagain getting its deserved place.

Apart from Muddupalani, six other women are authors of various dramas and poetry. Umayamba Thampuratti, the mother of the famous artist Raja Ravi Varma, was from the famous Kilimanoor Kshatriya family in Travancore. As per tradition, all women in the family used to get a good education. Umayamba was a talented poet and wrote Parvati Swayamvaram, which was published by Raja Ravi Varma.

Some of them are prolific writers. Triveni, daughter of Ananta Acarya of Udayendrapura (Tamilnadu), author of the Yadava-Raghava-Pandaviya, has written two dramas and 6 poems. Kutti Kunju Thankachi has authored 18 compositions, including Attakathas, poetry and plays. Thankachi had gained popularity as a poet during her time, and people used to visit her to read their poems to listen to her opinions. She is known to have good knowledge of music and composed songs in several ragas such as Kambhoji, Kalyaani, Naatta, Khamas and Surutti.

But the field of these women intellectuals is by no means limited to performing arts, play and poetry. They have handled diverse and complex subjects.

Laxmidevi Paygunde's 'Kal Madhav Laxmi' is a commentary on 'Kal Madhav' by Madhavacharya. It is a treatise on the proper time for performing various rites, but its philosophical part has a great discussion on the existence and nature of 'time'. Beginning from the objection, 'It may be said that there is no proof about the existence of time', Madhavacharya discusses the points concerning 'Shruti', e.g.

"The Vaisesikas say that Time is both eternal and indivisible; but Madhava says that Time is both eternal (Nitya) and created (Janya); both divisible (Savayava) and indivisible (niravayava). That Time is both produced and divisible is stated in the Narayaniya Upanisad.........the eternity of Time, according to the Vaisesikas, simply means that it exists up to the period of Dissolution; Time is partless and indivisible in the sense that its parts are not perceptible," etc. All these discussions directly remind us of the current debate in science about the existence and nature of time.

To write a commentary on such a subject implies thorough knowledge of such subtleties.

Laxmi Devi writes based on the Vedanta philosophy. Pranmanjari writes commentaryonTantra Sadhana. Both of them belong to families of Vedic scholars and write in Sanskrit. They are able life partners of their scholar husbands. An equally able life partner is Savitribai Phule, who carried the legacy of social reform from her husband, Mahatma Jyotirao Phule. It was obvious that the thrust of her poetry would be on social reforms. However, it should be noted that 7 of her poems are purely on the subjects of nature. The thoughts and work of this couple have made a deep impact on the social discourse of the 20th century.

Sahajo bai and Daya bai are themselves practicing yoginis and write from self-experience and the knowledge of yoga they have attained from their Guru. They write in Hindi. Venkatamamba wrote on Patanjal Yoga in Telugu.

Yet another class of women became so proficient in various branches of Darshan Shastras that they ran their schools. Hoti Vidyalankar was the daughter of a scholar; he gave her education, and she went on to start her own Sanskrit 'tol' or school. But after the death of her husband and her father, Hoti seems to be on her own for the rest of her life. Post the famine of 1770, she went from Bengal to Banaras to learn and by virtue of her merit, was able to start her own school in Banaras. She used to participate in the 'Vidvat sabha, ' the scholarly debates in Varanasi. Dravamayi Devi, daughter of Chandicharan Tarkalankar of the village of Barabari in Bengal, became a widow in childhood and began to read in the Tol (private Sanskrit School) of her father. Pleased with her extraordinary mastery over Vyakaran (Grammar), Chandicharan taught her Kavya (Poetry) and Alamkar-shastra (Rhetoric) and also some portion of Nyaya(logic). Dravamayi learnt in fourteen years what male students generally learn after twenty years’ study.

Devi Tarkalankara of Nudeeya (Nadia), had a college where Law or Dharmashastra was taught. The title 'Tarkalankara' (the one whose ornament is logic) implies knowledgeofNyaya and the teaching of Dharmashastra implies knowledge of Mimansa. Parvati Tarkabhushana of Thanthaniya in Calcutta, had a college where Nyaya and Smrti texts were taught.

Hotu Vidyalankar was sent by her father to her guru’s home in a neighbouring village for formal education. She decided not to marry, became proficient in Ayurveda and opened her own school. Many a practitioner of Ayurveda used to consult her.

Venkamamba was an exceptionally talented girl. From a very young age, Venkamamba would sit engrossed in devotion for hours and would compose and sing devotional songs extempore. She received formal education under the guru Subramanya Desika, who was quick to recognize her talent and intelligence and taught her on arangeofsubjects including Yoga. Venkamamba's fame became such that many potential grooms would back off because of her exceptional beauty and talent. She was content with being 'married to God. Finally, after a marriage which did not last the untimely death of her husband, she declined to undergo the ritual of shaving her head. Ostracized by the traditional section of society, she continued doing what she did best since childhood and produced many beautiful literary pieces, including plays, poetry, and Yakshgana etc. She became a devotee of Tirumala Tirupati, did her yog Sadhananear acave of Tirupati. Her Rajyog saram shows her mastery over Ashtang yoga. According to some accounts, she was instrumental in starting the free food service there. She made food and water available there every year for 10 days during the festival of Sri Narasimha Jayanthi. In her memory, there is now the Matrusri Tarigonda Vengamamba Anna Prasadam Centre in Tirupati today. A TV series and a movie have also been produced on the remarkable life of Tarigonda Venkmamba.

All those literary works are traditional in the sense that they conform with the established norms of poetry and play, outlined by Bharat Muni and other sages.

The literature of the new age can be seen in two women of this period. Kailashbashini Devi wrote her diary from 1846 onwards, which was later published as JanaikaGrihabadhu'r Diary( diary of a house wife). This, arguably, is the earliest one maintained by a woman in India. It was first serialized in the Bengali monthly, Basumati, in 1953, with the title ‘Janaika Grihabodhur Diary’(Diary of a Certain Housewife). The diary is written in an incohesive manner and informal language. After all, it was her chronicle. And yet there are insights. She refers to places in traditional names, disregarding the names used by the British for their new administrative divisions. Thus Rajshahi isRampur to her and Barrackpore is Chanok. Her sense and knowledge of history are displayed when Jahanabad in Midnapur reminds her that during the Sepoy Mutiny, the soldiers of the Badshah of Delhi, Bahadur Shah Zafar-II, stayed there. She adds that before this, even the Mughals and the Pathans fought at this place. The dilemmas faced by educated people of that generation, whether Hindu rituals are meaningful, whether God-worshipping is logical, are also echoed in her diary pages.

Krishna Kamini Dasi's Chittabilasini Nama, a collection of her poems published in 1856 CE, is modern in the sense that it deals with subjects like comic poem about the arrival of railways much to the consternation of the gods and goddesses; and a remarkable dialogue between two young widows about the then recently passed Widow Remarriage Act. The language of her poems is delightful, colloquial and easy Bangla. However, her short and crisp introduction shows the depth of her thinking.

The gist of her introduction is as follows:

The land where language, literature and culture do not flourish should be called a jungle even if people live there. This land called Punyabhumi was rich with prose and poetry of the highest quality. The tradition of literature created by Valmiki, Bhavabhuti, Kalidas, etc., could not survive under Islamic rule. If we want to restore our glory, our literary tradition must be revived. Women's contribution to this process is essential. That is why I am writing this Chitta Vilasini. Please read this with love and empathy towardstheauthor. This is the first book by a woman in this modern period. It can be ridiculed, but I have enough courage to take the risk. For praising or even for criticizing, if this book inspires other women to come forward and write, it will be a fortunate and welcome turn to restore our national glory.

Bharati Web