Women Intellectuals and Authors of Ancient & Medieval India: II

Total Views |

(This article is the second in a series by Milind Oak exploring the intellectual and literary contributions of women in India from 1 CE to 1857. The series will cover the status of women’s education across different periods, notable women intellectuals and authors, and their literary achievements in various fields, including poetry, philosophy, and religious discourse. It aims to bring forth the often-overlooked contributions of women to India's intellectual and cultural heritage.)

Status of Education of Women (1 CE-1857)

Education for princesses, daughters of ministers and other affluent classes

The women in affluent classes of society, the Queens, and the women in Court were educated. It was not an accident. They were part of the tradition. There are multiple references to women's education in this period's literature.

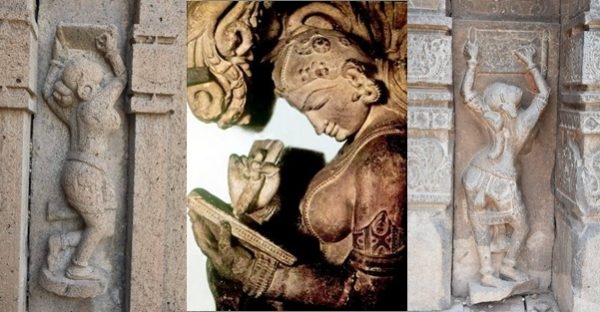

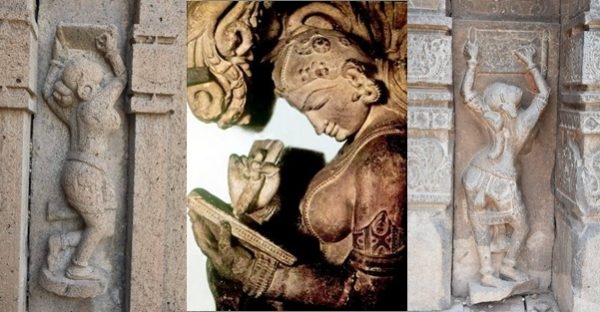

Source: MyIndiaMyGlory

The Vatsyayan Kamsutra mentions,

Courtesans, princesses and daughters of ministers who had attained great proficiency in Sastras.

In Lalit Vistara, the Sanskrit biography of Bhagvan Buddha written in about 1st Century CE, Siddhartha Goutam is asked about the qualities he would like to have in his wife. He answers,

The one who can write meaningful composition. LalitVistara., Chap. 12

The Harsacarita of Bana reveals that Rajyasri, the sister of King Harsa, got education and training in various arts, including dancing and singing, along with the guidance of their guru Divakaramitra.

Various inscriptions and epigraphs reflect women's education for royal families.

In Kuknur plates of Narasimha II of the Western Gangas (found in Yellurga Taluq, Raichur district, Karnataka) of CE 968–9, verses 46–49 are devoted to Kundanasami’seulogy, highlighting her physical charms, wholesome beauty, her accomplishmentsinlearning and the fine arts, her patronage to the erudite and the deserving, her deepdevotion to Jaina and her knowledge of Jaina philosophy. Kundanasami was the elder sister of Ganga-Kandarppa and was married to King Rajaditya of Chalukya lineage.

The 64 kalas enumerated in Kamasutra (I, 3. 16) included prahelikas (composing and solving riddles and rhymes), pustakavacana (reading from books) and kavyasamasya-purāṇa (composing an instant lyrical reply to a query). To acquire such intellectual capacity, there was an elaborate curriculum. The curriculum of studies for these women in the ninth century CE included Vatsayayana Kamsutra, Dattaka, Vitaputra, and Rajaputra, the Natyashastra of Bharata, Visakhila’s treatise on art, Dantila’s workonmusic, Vrikshayurveda, painting, needlework, woodwork, metalwork, clay modelling, cookery and practical training in instrumental music, singing and dancing. Visakhilaand Dantila are earlier scholars of Natya Shastra and music who are frequently quoted by renowned scholars like Bharat Muni, Abhinavagupta, Krishnaswami (the commentator of the Amara-kosa), etc.

Rajshekhar( 9th Century CE) in his Kavya Mimansa says,

Like men, women, too, can be poets. Genius inheres in self, irrespective of sex differences between men and women.

Bilhana, the famous poet of 11th Century CE, extols the women of Kashmir for their learning, which allowed them to speak both Sanskrit and Prakrit.

There are some inscriptions mentioning women priestesses also. We find an inscription where. In CE 1005, six maṭṭars of land were granted to Revabbe Gauravi of Mulasthana at the request of the eight gāvuṇḍas and the sixty tenants of Sirivur in Karnataka.

learned women are reflected in the literature of this period.

We find a direct reference to women wearing the holy thread (yagyopavita) in Banabhatta’s Kadambari (7th century CE). Here, Mahashweta is described as one whose body has been rendered pure by the wearing of a brahma-sütra or holy thread.

From the Uttara Rama-charita (Act II) of Bhavabhuti (8th Century CE), we come to know that Atreyi resided in the hermitage of Valmiki with Lava and Kusha and studied the Vedic literature with them. But when she could not keep pace with those exceptionally intelligent boys, she left the hermitage and travelled from the north to the Dandaka forest in the south to learn the Vedanta from Agastya and other sages. Malati-Madhava of Bhavabhuti (Act I) again, the Buddhist nun Kamandaki herself narrates that people from all parts of the country flocked to her place for instruction and coaching.

The Prabandha Chintamani (13th Century CE) mentions a story. The door keeper informs Bhoja that a scholarly family has come to meet him. When he gives permission, the dasi (servant) of the family enters and says that the father, his wife, his son, and his daughter all are scholars. So much so that this Kani dasi, who has come to inform you this, is also a scholar. To test them, king Bhoj asks each one of them a 'Samasya',(aformofPrahelika). All of them give satisfactory answers. The daughter answers in such beautiful poetry that king Bhoj accepts her as her wife.

Obviously, the characters in these dramas and plays are fictional, but they certainly reflect the social reality of those times.

But literature and performing arts were not the only fields for women in that period. There was a Kashkritsni somewhere between the 1st to 4th century CE who wrote a treatise on the Mimansa Shastra. Among the Hindu works translated into Arabic in the 8th century AD, there was a book on midwifery written by a lady doctor whose name appears as Rusa in the Arabic version.

The grandmother of Mahadamba or Mahadaisa(13th Century CE), the Mahanubhavscholar, was also a scholar. Her name was also Mahadaisa, which was probably given to her granddaughter. Vamanacharya was her husband. Vamanacharya and his wife acted as priests to the royal family of Devagiri. Once, some pandits from other provinces came to Devagiri for debate, and Mahadaisa refuted their arguments so successfully that King Mahadeo was very much pleased and made her a grant of five villages.

Ratnakheta Srinivasa Diksita was the court poet of Surappa (16th Century CE): Ratnaketa Dikshita’s wife and the mother-in-law of renowned scholar Appaya Dikshit was also a scholar and poet. The story goes that some pandits once came from the north with a view to invite Sri Dikshita to debate. They reached his house in the early morning and found his wife sprinkling the house garden with water. On making enquiries of her, she sensed their intentions and replied in poetic verses. The pandits who heard them, composed on the spur of the moment, were stunned at her literary ability and gave up attempts to engage Sri Dikshita in debate and went away.

The 17th-century historical poem Raghunathabhyudaya specifically mentions that the Nayaka King Raghunatha encouraged female education in his family as well as outside.

Status of Education of Women (1 CE-1857)

Education for princesses, daughters of ministers and other affluent classes

Source: MyIndiaMyGlory

The Vatsyayan Kamsutra mentions,

संत्यपि खलु शास्त्रप्रहतबुद्धयो गणिकाः राजपुत्र्यो महामात्यदुहितरश्च कामसूत्र ।. 3.12.

Courtesans, princesses and daughters of ministers who had attained great proficiency in Sastras.

In Lalit Vistara, the Sanskrit biography of Bhagvan Buddha written in about 1st Century CE, Siddhartha Goutam is asked about the qualities he would like to have in his wife. He answers,

सा गाथ लेख लिखिते गुण अर्थ युक्ता। या कन्या ई दृश भर्वेमम तां वरेथाः ।।

The one who can write meaningful composition. LalitVistara., Chap. 12

The Harsacarita of Bana reveals that Rajyasri, the sister of King Harsa, got education and training in various arts, including dancing and singing, along with the guidance of their guru Divakaramitra.

Various inscriptions and epigraphs reflect women's education for royal families.

In Kuknur plates of Narasimha II of the Western Gangas (found in Yellurga Taluq, Raichur district, Karnataka) of CE 968–9, verses 46–49 are devoted to Kundanasami’seulogy, highlighting her physical charms, wholesome beauty, her accomplishmentsinlearning and the fine arts, her patronage to the erudite and the deserving, her deepdevotion to Jaina and her knowledge of Jaina philosophy. Kundanasami was the elder sister of Ganga-Kandarppa and was married to King Rajaditya of Chalukya lineage.

The 64 kalas enumerated in Kamasutra (I, 3. 16) included prahelikas (composing and solving riddles and rhymes), pustakavacana (reading from books) and kavyasamasya-purāṇa (composing an instant lyrical reply to a query). To acquire such intellectual capacity, there was an elaborate curriculum. The curriculum of studies for these women in the ninth century CE included Vatsayayana Kamsutra, Dattaka, Vitaputra, and Rajaputra, the Natyashastra of Bharata, Visakhila’s treatise on art, Dantila’s workonmusic, Vrikshayurveda, painting, needlework, woodwork, metalwork, clay modelling, cookery and practical training in instrumental music, singing and dancing. Visakhilaand Dantila are earlier scholars of Natya Shastra and music who are frequently quoted by renowned scholars like Bharat Muni, Abhinavagupta, Krishnaswami (the commentator of the Amara-kosa), etc.

Education for general women

Rajshekhar( 9th Century CE) in his Kavya Mimansa says,

पुरूषवत् योषितोऽपि कवी भवेयुः । संस्कारो ह्यात्मनि समवैति, न स्त्रैणं पौरुषं वा विभागमपेक्षते ।

Like men, women, too, can be poets. Genius inheres in self, irrespective of sex differences between men and women.

Bilhana, the famous poet of 11th Century CE, extols the women of Kashmir for their learning, which allowed them to speak both Sanskrit and Prakrit.

There are some inscriptions mentioning women priestesses also. We find an inscription where. In CE 1005, six maṭṭars of land were granted to Revabbe Gauravi of Mulasthana at the request of the eight gāvuṇḍas and the sixty tenants of Sirivur in Karnataka.

learned women are reflected in the literature of this period.

We find a direct reference to women wearing the holy thread (yagyopavita) in Banabhatta’s Kadambari (7th century CE). Here, Mahashweta is described as one whose body has been rendered pure by the wearing of a brahma-sütra or holy thread.

From the Uttara Rama-charita (Act II) of Bhavabhuti (8th Century CE), we come to know that Atreyi resided in the hermitage of Valmiki with Lava and Kusha and studied the Vedic literature with them. But when she could not keep pace with those exceptionally intelligent boys, she left the hermitage and travelled from the north to the Dandaka forest in the south to learn the Vedanta from Agastya and other sages. Malati-Madhava of Bhavabhuti (Act I) again, the Buddhist nun Kamandaki herself narrates that people from all parts of the country flocked to her place for instruction and coaching.

The Prabandha Chintamani (13th Century CE) mentions a story. The door keeper informs Bhoja that a scholarly family has come to meet him. When he gives permission, the dasi (servant) of the family enters and says that the father, his wife, his son, and his daughter all are scholars. So much so that this Kani dasi, who has come to inform you this, is also a scholar. To test them, king Bhoj asks each one of them a 'Samasya',(aformofPrahelika). All of them give satisfactory answers. The daughter answers in such beautiful poetry that king Bhoj accepts her as her wife.

Obviously, the characters in these dramas and plays are fictional, but they certainly reflect the social reality of those times.

But literature and performing arts were not the only fields for women in that period. There was a Kashkritsni somewhere between the 1st to 4th century CE who wrote a treatise on the Mimansa Shastra. Among the Hindu works translated into Arabic in the 8th century AD, there was a book on midwifery written by a lady doctor whose name appears as Rusa in the Arabic version.

The grandmother of Mahadamba or Mahadaisa(13th Century CE), the Mahanubhavscholar, was also a scholar. Her name was also Mahadaisa, which was probably given to her granddaughter. Vamanacharya was her husband. Vamanacharya and his wife acted as priests to the royal family of Devagiri. Once, some pandits from other provinces came to Devagiri for debate, and Mahadaisa refuted their arguments so successfully that King Mahadeo was very much pleased and made her a grant of five villages.

Ratnakheta Srinivasa Diksita was the court poet of Surappa (16th Century CE): Ratnaketa Dikshita’s wife and the mother-in-law of renowned scholar Appaya Dikshit was also a scholar and poet. The story goes that some pandits once came from the north with a view to invite Sri Dikshita to debate. They reached his house in the early morning and found his wife sprinkling the house garden with water. On making enquiries of her, she sensed their intentions and replied in poetic verses. The pandits who heard them, composed on the spur of the moment, were stunned at her literary ability and gave up attempts to engage Sri Dikshita in debate and went away.

The 17th-century historical poem Raghunathabhyudaya specifically mentions that the Nayaka King Raghunatha encouraged female education in his family as well as outside.

But perhaps the greatest evidence of common women conquering intellectual fields comes from the women authors we will be reviewing here.

This series highlights how Indian women across centuries have made significant contributions to literature, education, and philosophy. Their presence in various fields challenges the notion that women's education and intellectualism were absent in earlier times. In the next part, we will explore the status of women's education from 1 CE to 1857, examining historical records, inscriptions, and literary references that provide insights into how women acquired knowledge and participated in scholarly discourse.

To read the first article, click here