The Curious Case of ‘Tasdiq’: Is Karnataka’s Bureaucracy Still Stuck in Mughal Era?

Total Views | 61

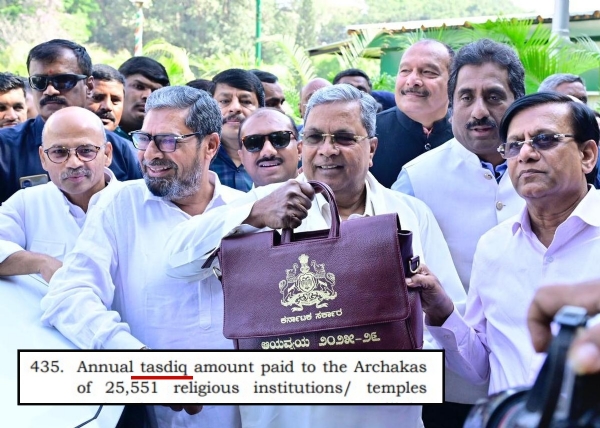

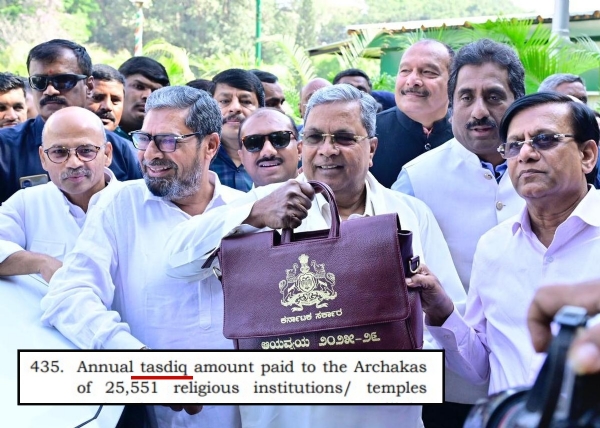

The term "tasdiq," (also spelt or “tasthik” or “tastik”) has inexplicably found its way into the administrative lexicon of Karnataka, raising serious concerns about linguistic and cultural imposition. Shockingly, in the Karnataka Budget 2024-2025, this foreign-origin word was used about the increased financial support (tasdiq amount) allocated to Archakas (priests) serving in Hindu temples under the Endowment Department. The Karnataka government has been employing this term in official documents and websites for an extended period, a practice unquestioningly adopted by various media outlets. However, its usage raises questions about its origins and relevance, particularly in the context of Hindu temples.

Language reflects cultural identity and historical evolution. In India, a nation characterised by its linguistic diversity, the administrative language has been influenced by various foreign dominations, including Persian, Arabic, and English. The incorporation of terms like "tasdiq" into official usage exemplifies this phenomenon.

The term is rooted in Arabic, meaning truth, and in the Persian language it means confirmation. During the medieval period, Persian significantly influenced the Indian subcontinent's administrative and legal systems, especially under the Mughal Empire. In regions like Karnataka, which experienced various dynastic rules, including the Persian-influenced Deccan Sultanates, terms like "tasdiq" were assimilated into the administrative vocabulary to denote official confirmation or certification. Notably, under rulers such as Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, Persian was the official language of administration, further embedding such terms into the bureaucratic framework. Noted researcher Krishna Kolhar Kulkarni had said the Adilshahi rulers of Vijayapura had promoted creation of literature in Arabic and Persian during the period in Karnataka.

The British colonial era further transformed India's administrative language, introducing English as the medium of governance. However, pre-existing Persian and Arabic terms persisted, especially in legal and land revenue contexts. This influence remains evident in legal documents such as First Information Reports (FIRs), which still incorporate Urdu-Persian terminology in police operations, charge sheets, and general diaries.

Currently, the Karnataka government uses the term "Tasdiq Amount" which refers to the officially approved financial assistance or honorarium paid annually to temple priests by the Karnataka government. On the state government’s website of Hindu Religious Institutions and Charitable Endowments Department, it is written that Compensation in form of “Tasdik” is being paid to the Religious Institutions for their lands vested with the government under Karnataka Inam Abolition Act 1955 section 21 and Karnataka other Inam abolition Act 1977. It is pertinent to mention that many religious institutions in Karnataka historically owned Inam lands (granted lands) under royal patronage. And, these Acts abolished these land grants and transferred ownership to tenants or the government.

The use of terms like tasdiq — associated with approvals, grants, and compensations — raises several questions. Were the Islamic rulers giving “tasdiq” to the religious institutions? Moreover, why is there the persistent use of Islamic and Persian-origin terms in Karnataka’s governance structure? Is it merely a continuation of historical administrative language, or does it reflect an underlying effort to retain Islamic governance structures, particularly in revenue administration and temple management?

For instance, terms such as "Sanad" (certificate) and "Roznamcha" (daily register) continue to be used in Karnataka's revenue and temple administration. These terms may have historical roots because of past administrative practices of Islamic and Mughal invaders. However, using them for Hindu temples today should not necessarily align with efforts to preserve native languages.

The Karnataka Congress government frequently opposes the use of Hindi, citing linguistic and cultural preservation, yet it has no hesitation in incorporating Arabic and Persian words such as tasdiq into official documents, especially in matters related to Hindu temples. This selective outrage against Hindi exposes their double standards. Why should a term with clear non-Hindu roots be imposed upon the sacred traditions of Hindu temples? This is yet another instance of how India’s indigenous Hindu identity is being diluted through subtle linguistic distortions. It is imperative that our heritage, culture, and language remain untainted by external influences, especially in matters concerning Sanatan Dharma.

If their stance were truly about protecting Karnataka’s linguistic heritage, shouldn’t they be promoting Sanskrit-origin terms for Hindu religious affairs instead of using words with Islamic connotations? This deliberate imposition of foreign terminology, while rejecting Hindi under the guise of regional pride, only strengthens the argument that their opposition is politically motivated rather than genuinely rooted in cultural preservation.

This hypocrisy raises an important question: Is the Karnataka Congress government truly committed to protecting Kannada and indigenous Indian culture, or is their language politics merely a tool to selectively push certain ideological narratives?

Language reflects cultural identity and historical evolution. In India, a nation characterised by its linguistic diversity, the administrative language has been influenced by various foreign dominations, including Persian, Arabic, and English. The incorporation of terms like "tasdiq" into official usage exemplifies this phenomenon.

The term is rooted in Arabic, meaning truth, and in the Persian language it means confirmation. During the medieval period, Persian significantly influenced the Indian subcontinent's administrative and legal systems, especially under the Mughal Empire. In regions like Karnataka, which experienced various dynastic rules, including the Persian-influenced Deccan Sultanates, terms like "tasdiq" were assimilated into the administrative vocabulary to denote official confirmation or certification. Notably, under rulers such as Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, Persian was the official language of administration, further embedding such terms into the bureaucratic framework. Noted researcher Krishna Kolhar Kulkarni had said the Adilshahi rulers of Vijayapura had promoted creation of literature in Arabic and Persian during the period in Karnataka.

The British colonial era further transformed India's administrative language, introducing English as the medium of governance. However, pre-existing Persian and Arabic terms persisted, especially in legal and land revenue contexts. This influence remains evident in legal documents such as First Information Reports (FIRs), which still incorporate Urdu-Persian terminology in police operations, charge sheets, and general diaries.

Currently, the Karnataka government uses the term "Tasdiq Amount" which refers to the officially approved financial assistance or honorarium paid annually to temple priests by the Karnataka government. On the state government’s website of Hindu Religious Institutions and Charitable Endowments Department, it is written that Compensation in form of “Tasdik” is being paid to the Religious Institutions for their lands vested with the government under Karnataka Inam Abolition Act 1955 section 21 and Karnataka other Inam abolition Act 1977. It is pertinent to mention that many religious institutions in Karnataka historically owned Inam lands (granted lands) under royal patronage. And, these Acts abolished these land grants and transferred ownership to tenants or the government.

The use of terms like tasdiq — associated with approvals, grants, and compensations — raises several questions. Were the Islamic rulers giving “tasdiq” to the religious institutions? Moreover, why is there the persistent use of Islamic and Persian-origin terms in Karnataka’s governance structure? Is it merely a continuation of historical administrative language, or does it reflect an underlying effort to retain Islamic governance structures, particularly in revenue administration and temple management?

For instance, terms such as "Sanad" (certificate) and "Roznamcha" (daily register) continue to be used in Karnataka's revenue and temple administration. These terms may have historical roots because of past administrative practices of Islamic and Mughal invaders. However, using them for Hindu temples today should not necessarily align with efforts to preserve native languages.

The Karnataka Congress government frequently opposes the use of Hindi, citing linguistic and cultural preservation, yet it has no hesitation in incorporating Arabic and Persian words such as tasdiq into official documents, especially in matters related to Hindu temples. This selective outrage against Hindi exposes their double standards. Why should a term with clear non-Hindu roots be imposed upon the sacred traditions of Hindu temples? This is yet another instance of how India’s indigenous Hindu identity is being diluted through subtle linguistic distortions. It is imperative that our heritage, culture, and language remain untainted by external influences, especially in matters concerning Sanatan Dharma.

If their stance were truly about protecting Karnataka’s linguistic heritage, shouldn’t they be promoting Sanskrit-origin terms for Hindu religious affairs instead of using words with Islamic connotations? This deliberate imposition of foreign terminology, while rejecting Hindi under the guise of regional pride, only strengthens the argument that their opposition is politically motivated rather than genuinely rooted in cultural preservation.

This hypocrisy raises an important question: Is the Karnataka Congress government truly committed to protecting Kannada and indigenous Indian culture, or is their language politics merely a tool to selectively push certain ideological narratives?