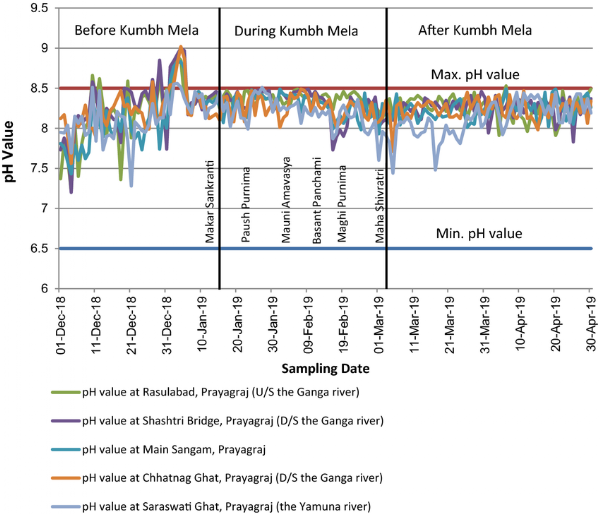

The overwhelming response to the Mahakumbh and crores of Hindus across globe gathering to take a holy dip in Ganga has raised a serious question—does the growing influence of Hinduism seem unsettling to certain sections of society? There has been a continuous attempt, through various media platforms, to warn devotees visiting the Ganges about the

risk of bacterial and skin infections. But how much truth lies in these claims?

Scientific research conducted over the years on the properties of Ganga Jal provides a strong counterargument. What makes Ganga Jal unique, and why is it considered so sacred in Hinduism? Let’s explore and understand its remarkable qualities.

Facts about the holy river & the holy dip

Ganga originates from Gangotri in Uttarakhand and is a unique freshwater ecosystem that travels approximately 2,525 km before merging into the Indian Ocean through the Bay of Bengal. The confluence point is known as Ganga Sagar (West Bengal). Along its journey, the sacred river nourishes almost the entire northern and parts of eastern India, holding immense significance in the lives of millions.

However, during the Mahakumbh, when Hindus from across the world gather to take a holy dip in the Ganga, there is a persistent narrative being pushed—that the river’s water is not only impure but also unfit for human health. But what does scientific research say about the so-called "questionable purity" of Ganga Jal? Let’s see what scientific research suggests;

What have scientists discovered over ages about 'Ganga'?

Geographical

research has revealed that the Himalayas were formed at the very site where the Tethys Ocean once existed, due to the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. This establishes the ancient link between the Himalayas and the ocean, which also explains the discovery of marine fossils at great altitudes in the mountain range.

Scientific studies have further confirmed the remarkable antibacterial properties of Ganga water. One of the most significant proofs of this phenomenon is its

ability to retain high levels of dissolved oxygen even in highly polluted environments. The first recorded discovery of this unique trait was made by

British bacteriologist Ernest Hankin in 1896. His research demonstrated that cholera bacteria, which thrive in regular tap water, were rapidly destroyed upon contact with Ganga water.

To examine this further, Hankin conducted an experiment using two samples of Ganga water—one was boiled, and the other was filtered. His findings were fascinating: the filtered water retained its antibacterial properties, while the boiled water lost them. This led to the conclusion that the element responsible for Ganga’s bactericidal nature is heat-sensitive.

Nearly two decades later, in 1916, Canadian microbiologist Félix d’Hérelle, while researching at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, discovered and explained the structure of bacteriophages (phages)—viruses composed of a protein outer shell containing genetic material inside. Interestingly, these phages also exhibited heat-sensitive properties, which perfectly aligned with Hankin’s earlier discoveries.

The self-purifying and self-regenerating ability of Ganga Jal was nothing short of astonishing for Western scientists.

This divine purity is precisely why no Hindu ritual is considered complete without the use of Ganga Jal.

The deep reverence for the river in Sanatan Dharma reflects the profound knowledge ancient Indian sages possessed about its unique properties. When we connect this scientific research with the descriptions of the Ganges in the Vedas, it truly feels like there is ‘heaven in the Ganges.’

--