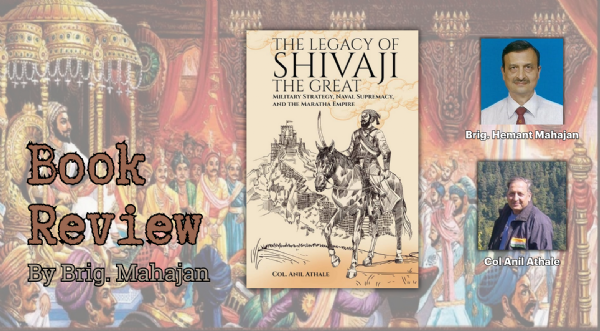

Book Review - PART 2: The Legacy of Shivaji The Great: Military Strategy, Naval Supremacy and the Maratha Empire by Col Anil Athale

Shivaji’s reign ended in 1680, but his legacy continued. He foresaw the threat posed by the English, and the Marathas later engaged the British in naval warfare.

Total Views |

One of the most compelling sections of the book is Athale's exploration of Shivaji's efforts to establish naval supremacy. The author details the formation of the Maratha navy and how it became a formidable force in the Arabian Sea, challenging the dominance of established powers like the Portuguese and the Siddis. This naval aspect of Shivaji's reign is often overshadowed by his land campaigns, but Athale brings it to the forefront, arguing convincingly that Shivaji's vision extended beyond terrestrial conquests to control maritime trade routes and secure coastal defenses.

Shivaji's Military Legacy

Shivaji's relentless offensive strategies, emphasis on political objectives in warfare, and vision of pan-Indian Hindu unity laid the groundwork for future Maratha victories. His successors fought and eventually defeated Aurangzeb's forces after a prolonged 25-year conflict.

A Visionary Leader and His Enduring Legacy

Shivaji’s reign ended in 1680, but his legacy continued. He foresaw the threat posed by the English, and the Marathas later engaged the British in naval warfare. Admiral Kanhoji Angrey's leadership kept the English at bay on the western coast, securing Maratha dominance in the region. Without Shivaji's efforts, the subcontinent might have become part of a continuous Islamic belt stretching from Morocco to Indonesia.

Chapter 3-Conflict at Sea (1679-1756)

Opposition on the Western Coast

The British encountered naval resistance only along the western coast of India, specifically from the Marathas. In contrast, their sea approaches in Calcutta and Madras faced little to no opposition.

Shivaji's Naval Vision

Shivaji was the first modern Indian ruler to recognize the importance of naval power. He built a navy from scratch, understanding that control of the seas was crucial for defending his kingdom and securing trade routes.

The Rise of Kanhoji Angrey

Kanhoji Angrey, born in 1669, played a pivotal role in strengthening the Maratha navy. Under his leadership, the Marathas established four shipbuilding yards, making them a formidable force at sea. His naval strategies were innovative and effective.

Maratha Naval Tactics

One of the Marathas' favoured methods was to shadow British ships and launch surprise attacks from the rear. They avoided exposing their broadsides, preferring to use a large number of smaller ships to overwhelm larger enemy vessels. This tactic was reminiscent of the "wolf pack" strategy employed by German U-boats during World War II.

British Attempts to Subdue the Maratha Navy

Beginning in 1716, the British made several attempts to weaken the Maratha navy by attacking their stronghold at Vijaydurg. Despite these efforts, the Marathas remained a powerful naval force for several decades.

Decline of the Maratha Navy

Peace prevailed between the Marathas and the British until 1756, when internal dissensions among the Marathas allowed the British, in collaboration with the Peshwa, to destroy the Maratha navy. Kanhoji Angrey had died in 1729, and without his leadership, the navy eventually crumbled.

Strategic Importance of the Maratha Navy

The powerful Maratha navy, under the leadership of Kanhoji Angrey, played a crucial role in protecting the western coast of India. Had it not been for the Maratha naval presence, Bombay might have become the capital of the East India Company instead of Calcutta.

Siege of Bassein

On May 15, 1739, after nearly two years of siege, the Marathas successfully captured the Portuguese stronghold of Bassein, marking a significant victory in their naval campaign.

British Victory and the Fall of the Maratha Navy

The eventual defeat of the Maratha navy by the British left the western coast under British control. The Marathas lost their ability to maintain contact with the west, a significant blow to their influence. This defeat highlighted a recurring issue in Indian history: personal egos and internal conflicts often obscured the larger strategic picture. Financially weak and politically fragmented, the Maratha Peshwas struggled to maintain central authority, with rich provinces controlled by generals who rarely contributed their share of revenue. As history has shown, a strong and financially stable central authority is crucial for a nation's long-term success.

Chapter 4-Panipat 1761 and the Power Vacuum in India

Transfer of Power to the Peshwas

After the death of Chhatrapati Shahu in 1749, a meeting was convened by Nanasaheb Peshwa and attended by Maratha officials. It was unanimously agreed that all executive powers for governing the state would be transferred to the Peshwas, marking a significant shift in the power structure of the Maratha Empire.

Rise of Modern Governance Institutions

During this period, several modern governance institutions emerged, including village panchayats, the village headman, and revenue officials overseeing groups of villages. These systems, some of which continue to this day, provided stability and organization at the local level. Additionally, a diplomatic corps was established as the Peshwa needed ambassadors in various places, a practice that contributed to the emergence of modern diplomacy.

The Changing Composition of the Peshwa Army

The Peshwa’s army, known as the Huzurat, had three key components: artillery, primarily composed of Muslims and North Indians; infantry, also composed of Muslims and North Indians with firearms; and cavalry, which mainly consisted of part-time Maratha soldiers known as Shiledars. However, the introduction of war elephants into the army was a strategic misstep. Over time, the Maratha army lost its distinct character and became a mercenary force, critically dependent on regular pay.

Meritocracy to Hereditary Rule

Under Bajirao Peshwa, appointments were made based on merit, allowing talented individuals from humble backgrounds to rise to prominence. However, after his time, appointments became increasingly hereditary, diluting the merit-based system that had once been a hallmark of Maratha governance.

Breakdown of Alliances and Internal Conflicts

The Marathas had long maintained alliances with Rajput rulers since the time of Shivaji, but this policy changed under Nanasaheb Peshwa. Involvement in the succession dispute within the House of Jaipur, where Holkar and Shinde supported opposing factions, strained relations with the Rajputs. Additionally, disputes erupted between the Peshwas and other Maratha factions, such as the Gaekwads and Bhonsles, further weakening internal unity.

Strategic Importance of Punjab and Afghan Resistance

The invasion by Nadir Shah in 1740 forced the Marathas to recognize the strategic importance of Punjab. From 1753, a small Maratha garrison was stationed in Delhi to protect the Mughal emperor. However, the Afghans, seeking to restore their dominance, disliked the Maratha presence. Ahmad Shah Abdali, in particular, sought to re-establish Afghan supremacy in Delhi, aided by the Rohillas, a group of Afghans settled north of Delhi.

Maratha Campaign and the Battle of Panipat

In 1760, the Maratha army under Sadashiv Bhau, son of Chimnaji and brother of Bajirao, reached Delhi with an army of about 200,000. However, the political landscape was complicated by alliances and rivalries. The Marathas rejected the Jat ruler Surajmal’s candidature for the post of Prime Minister, opting instead for Shuja-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Awadh. This decision cost them the crucial support of the Jats and later, Shuja-ud-Daula also switched sides to join Abdali.

The terrain around Panipat, dominated by Muslims of Afghan descent, further complicated the Marathas’ efforts to secure supplies. Another blunder was carrying a large number of non-combatants, including women and families, which hindered their mobility.

Key Events in the Battle

The Marathas initially held the upper hand in the battle. However, a critical mistake occurred when dismounted Maratha cavalrymen broke ranks and engaged in close combat, forcing the artillery to cease firing. This proved fatal. When Vishwasrao, the eldest son of the Peshwa, was struck by a bullet, Bhau, distraught, left his elephant and joined the hand-to-hand combat. This loss of command led to the Marathas' near-victory turning into a rout.

Despite heavy casualties on both sides, Abdali’s forces managed to defeat the Marathas. However, on their return journey, Abdali’s army was attacked by Sikhs, who rescued many Maratha prisoners. Some Marathas even settled in the hills of the north, with many marrying Sikh soldiers.

Analysis and Long-Term Effects of the Panipat Defeat

Failure to Form Alliances: Bhau failed to follow Shivaji's policy of befriending the Rajputs, relying instead on Shuja-ud-Daula, a Shia ruler, to counter Sunni Abdali, overlooking the solidarity within the Islamic world.

Missed Opportunities: The Marathas missed crucial opportunities, such as failing to attack Abdali while he was crossing the Yamuna River. Instead, they were preoccupied with celebrating their earlier victory at Kunjpura, a premature celebration that proved costly.

Strategic Missteps: Unlike Shivaji or Bajirao, who would have travelled light, the Marathas were burdened by the large number of families that accompanied the army. A considerable force under Malharrao Holkar was assigned to protect them, diverting valuable manpower from the battlefield.

Loss of Command: The death of Vishwasrao and Bhau’s emotional reaction led to a collapse in leadership. Despite being on the brink of victory, the Maratha infantry broke ranks, and the battle quickly turned against them.

Impact on the Future of India

The Marathas’ near-victory at Panipat showed the strength of their fighting prowess, but their defeat shattered their offensive spirit. The Afghans, however, suffered so greatly that they abandoned their dreams of ruling Delhi and Hindustan. Abdali’s forces weakened, and Punjab soon came under the control of the Sikhs, who established a powerful state with its capital in Lahore.

The failure to harmonize the cavalry-based warfare of the Marathas with the infantry and artillery-based tactics of their enemies contributed to their defeat. The lack of strong alliances continued to plague the Marathas in their later struggles, including their wars against the British. The Panipat debacle stands as a reminder of the importance of unity, coordination, and strategic foresight in military campaigns.

Chapter 5-The End of the Mughal Empire (1772) and Prelude to the First Anglo-Maratha War (1774-1782)

Aftermath of the Peshwa's Death

The death of the Peshwa in 1761 created an opportunity for the Nizam of Hyderabad and Hyder Ali of Mysore to expand their influence. However, their attempts to exploit the situation were thwarted by the Marathas, who successfully repelled their advances, maintaining the integrity of Maratha power in the region.

Rise of Mahadji Shinde (Scindia)

Mahadji Shinde, born in 1727, emerged as a formidable leader under the reign of Peshwa Madhavrao. By 1769, alongside Tukoji Holkar, he reasserted Maratha dominance over Delhi and the Mughal Emperor, reviving their influence in North India. Shinde’s leadership marked a resurgence of Maratha power, restoring their hold over strategic regions.

Maratha Revenge on the Rohilla’s

In retaliation for the Rohilla’s support of Ahmad Shah Abdali during the Third Battle of Panipat, Mahadji Shinde led a decisive campaign against them. In one battle, nearly 15,000 Rohilla’s were killed. This victory cemented Maratha control from the banks of the Ganga-Yamuna rivers to the Sutlej, ushering in nearly 30 years of Maratha supremacy in northern India until 1803.

Internal Strife and the Death of Madhavrao

In 1772, Peshwa Madhavrao died and was succeeded by his younger brother Narayanrao. However, Narayanrao was assassinated in 1773, allegedly at the behest of his uncle, Raghunathrao. Justice Ramshastri Prabhune later convicted Raghunathrao for his involvement, further destabilizing the Maratha leadership.

The First Anglo-Maratha War Begins

On December 12, 1774, the British launched an attack on Sashti Island (modern-day Mumbai), marking the beginning of the First Anglo-Maratha War. The Marathas, outnumbered and outmatched by British naval supremacy, lost control of the island. This confrontation set the stage for a protracted conflict between the Marathas and the British East India Company.

The East India Company’s Financial Crisis

In 1772, the East India Company faced financial insolvency, narrowly avoiding collapse by securing a loan. The British Parliament subsequently tightened control over the Company’s operations. Despite the British vulnerability, the Marathas, suffering from internal divisions and depleted financial resources, were unable to capitalize on this opportunity. The breakdown of the traditional revenue-sharing system between local governments and the Maratha central authority further weakened their position.

Treaty of 1776 and Temporary Peace

In 1776, the Marathas and the British reached a temporary agreement. The Marathas retained control of Bassein, while the British held Sashti. Additionally, the British agreed to cease their support for Raghunathrao, who had been a contentious figure within the Maratha leadership.

External Threats and the Prospect of a Maratha-French Alliance

Meanwhile, the British faced another crisis, this time in their North American colonies, which had revolted against British rule. This conflict naturally attracted French involvement, which extended to India. The possibility of a Maratha-French alliance alarmed the British, adding a new dimension to the ongoing Anglo-Maratha rivalry.

Chapter 6 - British Attack on Poona and the Lost Opportunity for Victory

The British Ambition to Install Raghunathrao Peshwa

The British were determined to make Raghunathrao the Peshwa. Both the British and Maratha forces prepared for war. The book provides detailed accounts of these preparations.

The British Campaign and Maratha Countermeasures

The British assembled their forces with the intent to cross the Western Ghats and invade Pune. However, the Marathas cleverly disrupted the British lines of communication, forcing the British to reconsider their plans. In response, the British decided to withdraw under the cover of night. Nana Phadnavis's network of spies discovered this retreat, and as soon as the British began to pull back, the Maratha cavalry launched a swift attack from both flanks.

The Treaty of Wadgaon (1779)

Caught in a vulnerable position, the British were compelled to sue for peace. This resulted in the Treaty of Wadgaon in 1779, through which the British agreed to return all the territories they had captured since the Treaty of 1756.

Analysis: Lessons from the Battle of Salher and Shivaji Maharaj

Allowed The British To Retreat To Bombay

In the Battle of Salher (1672), Shivaji's generals showed no mercy to the Mughal forces, utterly crushing the enemy. Similarly, Shivaji Maharaj decisively defeated the enemy at Pratapgarh. However, in this instance, the Marathas allowed the British to retreat to Bombay rather than pursuing them to finish the conflict.

A Missed Opportunity to Evict the British from Bombay

The Marathas had a golden opportunity to strike at Bombay and drive the British out. The conditions were highly favorable, and a more decisive approach could have significantly altered the course of history. This scenario offers a vital lesson: learning from the military strategies of Shivaji Maharaj, who would never have let such an opportunity slip by.

The Resumption of Hostilities and the End of Maratha Unity

Hostilities resumed as soon as the Bengal Army reached Bombay. The Battle of Wadgaon marked the last time the Marathas fought unitedly against the British. Prior to this, in 1775, the Battle of Addas saw both sides claim victory. It was also the first time the British army faced the formidable Maratha cavalry and their main army.

Chapter 7-The Second Anglo-Maratha War: A Coalition Against the British

The Formation of the Anti-British Alliance

In 1780, the Marathas, Nizam, and Hyder Ali formed a formidable alliance against the British. The Marathas pledged to keep the British army under Colonel Goddard engaged, while Hyder Ali aimed to capture Madras. The Nizam promised to assist Hyder Ali, and the Bhonsles of Nagpur were to attack Bengal. The alliance agreed not to negotiate a separate peace with the British.

The Bhonsles and the British

Despite being part of the alliance, the Bhonsles of Nagpur had a strained relationship with the Peshwas. The Bhonsles believed they were equals to the Peshwas and, relying heavily on a paid army that was predominantly non-Maratha, were constantly in need of funds. Financial resources were crucial for any government.

The Bhonsles' army, marching towards Bengal, alarmed the British. The Bhonsles demanded a hefty sum of 20 lakhs, and after negotiations, an agreement was reached. During the negotiations, the British assembled a force to attack Mahadji Shinde in the north. The Bhonsles allowed the British forces to pass through Orissa to aid the Madras Presidency, which was under attack from Hyder Ali.

The Gaikwad's Defection

In 1780, Fateh Singh Gaikwad became the first Maratha general to accept British protection, weakening the alliance.

Meanwhile, the British and Marathas clashed at Malanggad, a mountain fort.

Maratha Victories and Limitations

Goddard captured Bassein in 1780, a significant loss for the Marathas. The British planned to attack Poona but failed, and the Marathas recaptured most of the coastal territories they had lost since 1774, except for Bassein and Sashti. This was a major defensive victory for the Marathas.

The Alliance's Shortcomings

Despite the Maratha victory against Goddard's army, the alliance was hampered by the Bhonsles' inactivity in Orissa and Mahadji Shinde's limited success in the north.

Conclusion

The book benefits from a wealth of primary and secondary sources, including historical documents, chronicles, and contemporary accounts. Col Anil Athale's meticulous research shines through, as he combines these sources with his own analysis and interpretations to present a well-rounded perspective on Shivaji's military exploits and the socio-political context of his time. The inclusion of maps, illustrations, and photographs enhances the reading experience, providing visual aids that aid in understanding the geographical and strategic aspects of various wars.

--