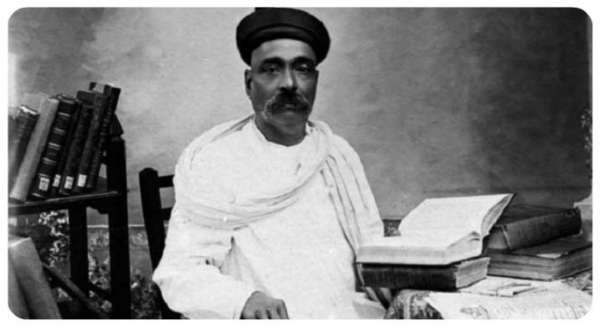

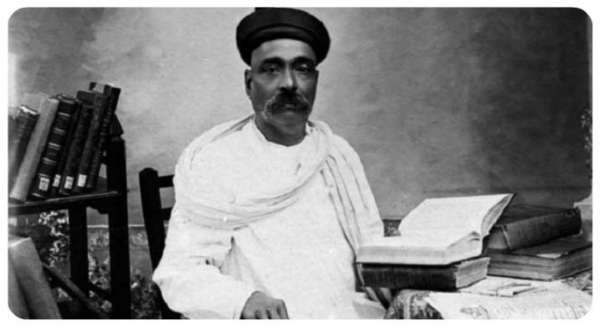

Lokmanya Tilak’s Significant Views on Economic Progress of Country

Total Views |

-Soham Thakurdesai

Whether a country is rich or poor, conquered or free, the majority of its inhabitants as a rule, earns its livelihood by manual labour. It cannot be said therefore the particular country has, economically speaking, improved so long as the conditions of the toiling majority in that country have not improved. - Lokmanya Tilak, Kesari 1881

Rajwade says – “The development of scientific knowledge in the nation is a prerequisite for the creation of an art of good quality weapon production. In those days Maharashtra lacked scientific knowledge. During Shahaji’s times in Europe, scientific thinkers/philosophers like Descartes, and Bacon were encouraging people to discover more and more about the basic elements of nature. And in Maharashtra saints like Eknath, Tukaram, Dasopant, Nipatniranjan were endeavouring to liberate people from nature’s (outer world’s) shackles to attain spiritual enlightenment. Is it surprising if such otherworldly people find screws, pins, guns and cannons repulsive? In short, in the words of Auguste Comte in those days Maharashtra was still in the Metaphysical state, and it was going to take another 500 years to reach the Positive state. Thus, in such a scenario when we couldn’t make our own technically advanced weapons, Shahaji had no choice but to buy them from others. (Translation mine).” [1]

Thus, such a societal apathy towards material progress right at the philosophical level stymied the scientific and hence the economic progress of the country. Lokmanya Tilak, the first mass leader of the Indian independence movement knew the history of his own country very well. He also knew the true nature of British imperialism. European colonial powers in general and particularly Great Britain could ride unhindered on the wave of economic prosperity because of the scientific advancement induced industrial revolution and forceful subjugation and economic drain of the colonized nations. Eminent economists and leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji, R. C. Dutt, G. V. Joshi et. al. propounded this “Drain Theory”. The excessive tax burden, and excessive expenditure on military and British bureaucratic salaries, and pensions were causing the primary drain.

This siphoned-off money would come back as investment by the British investors and then secondary drain would happen in the form of interest and dividends on such investments. It was the British government’s duty to set up industry in India, but it never cared to do that. Thus, it was a double whammy for the colonized nation. Tilak’s politics was about fighting this dual problem of British colonial excesses and Indian societal apathy. It was truly the politics of modern nation-building. Tilak through his erudite, persuasive arguments and a lifelong selfless industry successfully goaded his compatriots to shun the slumber of inaction and to wake up from the dream of other-worldly liberation at the cost of ignoring worldly progress. This is how his theory of Nishkam Karmyoga so lucidly and scholarly expounded in his seminal book Geetarahasya has become the bedrock of his political and economic thoughts and activities.

Lokmanya’s nationalism had various facets. Ganeshotsav, Shivajayantyotsav, his scholarly thesis on the antiquity of the Vedas, etc. represent the cultural and religious aspects of nationalism. The Crawford episode, criticism of the British administration’s biased and politically motivated handling of the Hindu- Muslim riots, spearheading the movement against the partition of Bengal on communal line (the VangaBhanga Andolan) etc. constituted the socio-political aspect of the same nationalistic expression. Lokmanya Tilak was successfully mobilizing the masses against British colonial rule on economic issues as well. As the leader of a colonized nation, he used economic nationalism to further political activism and mitigate the economic sufferings of his fellow countrymen by organising mass movements to oppose the government’s economic exploitation. In his lifetime Tilak faced three sedition trials. He was acquitted in the third one but the first one resulted in an 18-month imprisonment and the second one resulted in a 6-year imprisonment and exile in Mandalay, Burma. The reasons behind the trials and incarcerations were indeed political. But eminent historian Bipan Chandra has alluded to a possible economic angle to the first sedition case.

Following passage from his “The Rise and Growth of Economic Nationalism in INDIA”, warrants a full citation because it illuminates the role of economic issue-based agitation in Tilak’s politics and highlights his uniqueness as a politician of that era.

“Tilak began to tell the Deccan peasantry that there were laws designed to help them during famines, that the government was morally obliged to save their lives, that the officials were duty bound under the Famine Code to give them relief, that they must compel the officials to do so by firmly and loudly invoking the Code, and that they would be perfectly within their legal rights — they would in fact be helping the enforcement of laws —even if they were to refuse to pay the land tax when they were -not in a position to pay it. This was nothing but a rudimentary no-tax campaign and, in spite of Tilak's protestations to the contrary, was understood to be so by the government, which took energetic action against the agents of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, the Sabha itself, and in the end against Tilak himself. The fact that he was arrested in 1897 and sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment on the charge of sedition shows that the farsighted British officialdom was alarmed by the revolutionary potentialities of his campaign among the Deccan peasants in the winter of 1896. Moreover, Tilak himself clearly grasped the deep political implications of his work and drew appropriate political lessons from it. When his lead was not followed by other political workers and the Indian National Congress of 1896 also failed to take any active measures to help or arouse the victims of the famine, he denounced the Congress for its inactivity and wrote in the Kesari, dated 12 January 1897:

For the last twelve years we have been shouting (ourselves) hoarse, desiring that the Government should hear us. But our shouting has no more affected the Government than the sound of a gnat. Our rulers disbelieve our statements or profess to do so. Let us now try to force our grievances into their ears by strong Constitutional means. We must give the best political education possible to the ignorant villagers. We must meet them on terms of equality, teach them their rights and show how to fight constitutionally. Then only will the Government realise that to despise the Congress is to despise the Indian Nation. Then only will the efforts of the Congress leaders be crowned with success. Such a work will require a large body of able and single-minded workers to whom politics would not mean, some holiday recreation but an every-day duty to be performed with strictest regularity and utmost capacity.

He also showed awareness of the historic political role of the peasantry in a country like India. Thus, he declared -

The country's emancipation can only be achieved by removing the clouds of lethargy and indifference which have been hanging over the peasant, who is the soul of India. We must remove these clouds, and for that we must completely identify ourselves with the peasant— we must feel that he is ours and we are his.” [8]

This analysis clearly highlights Tilak’s role as people’s leader. Through his writings, speeches and agitations he was trying to safeguard the economic interests of his fellow countrymen and was trying to sow the seeds of broader unrest which would make the masses the bulwark of the agitation led by the Indian National Congress. Tilak had also expressed the now accepted political-economic theory that the famines are not natural. On the contrary they are manmade disasters. He succinctly writes –

It is meaningless to say that scanty rainfall causes famine. One who has even the rudimentary understanding of the economic principles about how the wealth is provided and distributed would not accept such excuses. (Translation mine)

Then he goes on to write –

Even after ten years of work people don’t have the savings which could sustain them for a year is the root cause of famine. (Translation mine)

He was emphasizing the point that the British political economy was the reason behind people’s lack of purchasing power.

Were Tilak’s endeavours only confrontational and agitational? Certainly not. He was supporting the enterprising Indians to establish an indigenous industry. He was also coaxing Indian workers to look at the international trade unions for inspiration to start unionism here in India. He was writing about the new economic ideas that had come out of Europe and their successful implementation in Asian nations like Japan. He wrote prolifically on economic topics like taxation, industry, trade, tariff, agriculture, labour, poverty, famine etc. The variegated economic topics that Tilak handled in his articles and

editorials are testimony of the importance that he attached to economics. In 1892-93 he wrote simple yet comprehensive and lucid articles on complex topics like the monetary system, exchange rate and silver-gold standards of coinage. They are an example of exemplary economic journalism. As established by noted historian Prof. J. V. Naik, Tilak’s article, written as early as 1883, introduced Karl Marx and his theories to the Indian readers for the first time. Authors have written about the influence of German economist Friedrich List on Justice Ranade’s economic thinking. [1][2][4] But we can find an independent (non-comprehensive) assessment of Listian economics in Indian context even in Lokmanya’s writings.[3]

In 1906 Lokmanya wrote a series of editorials about Irish Sinn Féin movement, its leader Arthur Griffin and economist Friedrich List’s influence on him. It is interesting that he was writing about it when the Swadeshi movement was in full swing. In his Calcutta tour he distributed pamphlets about the Sinn Féin movement.[9] Sinn Féin in Irish language means “We Ourselves”. The title of the article series was Amachech, Pan Kalel Tenva, it loosely translates as “Ours, only if we could understand it”. The first article compares Adam Smith’s economic theory with Friedrich List economic theory. Tilak rejects Adam Smith’s free trade-based economics and favours List’s nationalist economics. He argued that free trade would benefit only the rich nations and poor nations would only remain the source of raw material. At this backdrop he advocated the boycott of British goods and encouraged Swadeshi. Due to this economic foresight, even the ultimate political aim Swarajya wasn’t just about replacing the British bureaucracy with the Indian one, it’s about getting freedom to create national wealth.

The Lokmanya writes –

Swadeshi is God’s mandate. Swarajya doesn’t mean securing the fat salaried jobs, increasing national industry and production to contribute to the national wealth is the real meaning of Swarajya. (Translation mine).

Tilak was the first leader to recognize Maharashtra land’s potential to support the sugar industry. He wrote – “It is not possible for a nation’s financial wellbeing to depend all the time entirely on agriculture”. Thus, he advocated to make agriculture more profitable and to reduce people dependent on agriculture by generating other employment opportunities through industrialization. He walked the talk by supporting crowdfunding initiatives like Paisa Fund and raised capital for indigenous industries. He encouraged small and medium scale industries like matchbox factory, glass factory etc. He notes that post Franco-German war Germany was once again able to prosper due to its policy of raising small and medium enterprises scattered across the country.[10]

This is how he used the caste idiom to explain modern trade unionism. His English speech before the Madras workers demonstrates the quintessential Tilak style, where he uses the amalgamation of historical reference with the references of present-day scenarios in the world to drive home the point. He says –

Our ancient social and economic system was never designed in favour of the capitalist. Every trade had its own guild. That guild regulated the wages and disputes between the members of the guild, and that state of things is recorded in the books of Manu and Yagnavalkya. It is not a new doctrine; only you have to adopt that doctrine to the changed circumstances of the time. If you organise sufficiently and with a strong will our Indian Government will be compelled to recognise your unions.[12]

In the article, we have seen how Tilak advocated the ideas of a national system of political economy. So, was he then a dyed-in-the-wool economic nationalist? Or was he a closet capitalist as some of his modern day far-left detractors would like us to believe? Tilak fostered friendship with the Labour Party of England. Lenin condemned his Mandalay exile. Tilak praised Lenin’s Bolshevik revolution, but he was also of the opinion that Bolshevism wouldn’t succeed in India. He was the first honorary vice- president of AITUC (All India Trade Union Congress). So, does that mean he was a Marxist-Socialist or would have become one had he lived longer? There cannot be simple answers to these questions. We can venture an educated guess and say he would have been non-dogmatic in his economics as he was in his politics. We would have to probe further into his writings and utterances to understand more about the economic vision of the Lokmanya.

1. मराठे शाहीचा पाया घालणारा शहाजी, राजवाडे लेखसंग्रह, संपादक तकक तीर्क लक्ष्मणशास्त्री जोशी, साहहत्य अकादमी

2. Tilak: The Economist by T. V. Parvate

3. समग्र लोकमान्य हिळक, खंड ८, इंग्रजी आहण मराठी अग्रलेख आहण पत्रे, आमचेच - पण कळे ल तेंव्हा - १, २, ३, ४, ५ पान क्र.

५६५-५९५

4. आधुहनक भारत, आचायक शं. द. जावडेकर

5. Empire and the Economist: Analysis of 19th Century Economic Writings in Maharashtra: Neeraj Hatekar Economic and Political Weekly, Feb. 1-7, 2003, Vol. 38, No. 5 (Feb. 1-7, 2003), pp. 469-479

6. गीतारहस्य - बाळ गंगाधर हिळक

7. Lokmanya Tilak – Father of Indian Unrest and Maker of Modern India by D. V. Tamhankar.

8. The Rise and Growth of Economic Nationalism in INDIA – Bipan Chandra

9. लोकमान्य हिळक - धनंजय कीर पान क्र. २६२

10. https://maharashtratimes.com/editorial/samwad/economic-thought-of-the-lokmanya- tilak/articleshow/77156899.cms

11. समग्र लोकमान्य हिळक, खंड ८, इंग्रजी आहण मराठी अग्रलेख आहण पत्रे, पान क्र. 1343

12. समग्र लोकमान्य हिळक, खंड ८, इंग्रजी आहण मराठी अग्रलेख आहण पत्रे, पान क्र. 1320

Soham Thakurdesai studies and analyses Lokmanya Tilak's life, work and philosophy. He has written articles and poems that have been published in various Marathi and English newspapers, magazines and Diwali Ank. 2016 marked the centenary of Lokmanya Tilak's famous clarion call - Home Rule is my birthright and I shall have it. Maharashtra Government published a book of articles written by many eminet Tilak scholars. Soham has contributed an article to the book. He also delivers lectures and speeches on Lokmanya Tilak in Marathi and English.

Whether a country is rich or poor, conquered or free, the majority of its inhabitants as a rule, earns its livelihood by manual labour. It cannot be said therefore the particular country has, economically speaking, improved so long as the conditions of the toiling majority in that country have not improved. - Lokmanya Tilak, Kesari 1881

Eminent historian V. K. Rajwade poses an important question in an essay discussing the contribution of Shahaji Maharaj to the foundation of the Maratha Empire. Rajwade asks- while to his credit Shahaji Maharaj always ensured getting the latest advanced weaponry for his army, why he or any other leader during the medieval period didn’t create an indigenous system to produce advanced weapons domestically? The answer to this question exposes an Achilles’ heel of medieval Indian society. Notwithstanding his oft-repeated controversial commentary on many revered medieval saints his main observation still holds, and it is accepted as a historical fact.

Rajwade says – “The development of scientific knowledge in the nation is a prerequisite for the creation of an art of good quality weapon production. In those days Maharashtra lacked scientific knowledge. During Shahaji’s times in Europe, scientific thinkers/philosophers like Descartes, and Bacon were encouraging people to discover more and more about the basic elements of nature. And in Maharashtra saints like Eknath, Tukaram, Dasopant, Nipatniranjan were endeavouring to liberate people from nature’s (outer world’s) shackles to attain spiritual enlightenment. Is it surprising if such otherworldly people find screws, pins, guns and cannons repulsive? In short, in the words of Auguste Comte in those days Maharashtra was still in the Metaphysical state, and it was going to take another 500 years to reach the Positive state. Thus, in such a scenario when we couldn’t make our own technically advanced weapons, Shahaji had no choice but to buy them from others. (Translation mine).” [1]

Thus, such a societal apathy towards material progress right at the philosophical level stymied the scientific and hence the economic progress of the country. Lokmanya Tilak, the first mass leader of the Indian independence movement knew the history of his own country very well. He also knew the true nature of British imperialism. European colonial powers in general and particularly Great Britain could ride unhindered on the wave of economic prosperity because of the scientific advancement induced industrial revolution and forceful subjugation and economic drain of the colonized nations. Eminent economists and leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji, R. C. Dutt, G. V. Joshi et. al. propounded this “Drain Theory”. The excessive tax burden, and excessive expenditure on military and British bureaucratic salaries, and pensions were causing the primary drain.

This siphoned-off money would come back as investment by the British investors and then secondary drain would happen in the form of interest and dividends on such investments. It was the British government’s duty to set up industry in India, but it never cared to do that. Thus, it was a double whammy for the colonized nation. Tilak’s politics was about fighting this dual problem of British colonial excesses and Indian societal apathy. It was truly the politics of modern nation-building. Tilak through his erudite, persuasive arguments and a lifelong selfless industry successfully goaded his compatriots to shun the slumber of inaction and to wake up from the dream of other-worldly liberation at the cost of ignoring worldly progress. This is how his theory of Nishkam Karmyoga so lucidly and scholarly expounded in his seminal book Geetarahasya has become the bedrock of his political and economic thoughts and activities.

Lokmanya’s nationalism had various facets. Ganeshotsav, Shivajayantyotsav, his scholarly thesis on the antiquity of the Vedas, etc. represent the cultural and religious aspects of nationalism. The Crawford episode, criticism of the British administration’s biased and politically motivated handling of the Hindu- Muslim riots, spearheading the movement against the partition of Bengal on communal line (the VangaBhanga Andolan) etc. constituted the socio-political aspect of the same nationalistic expression. Lokmanya Tilak was successfully mobilizing the masses against British colonial rule on economic issues as well. As the leader of a colonized nation, he used economic nationalism to further political activism and mitigate the economic sufferings of his fellow countrymen by organising mass movements to oppose the government’s economic exploitation. In his lifetime Tilak faced three sedition trials. He was acquitted in the third one but the first one resulted in an 18-month imprisonment and the second one resulted in a 6-year imprisonment and exile in Mandalay, Burma. The reasons behind the trials and incarcerations were indeed political. But eminent historian Bipan Chandra has alluded to a possible economic angle to the first sedition case.

Following passage from his “The Rise and Growth of Economic Nationalism in INDIA”, warrants a full citation because it illuminates the role of economic issue-based agitation in Tilak’s politics and highlights his uniqueness as a politician of that era.

“Tilak began to tell the Deccan peasantry that there were laws designed to help them during famines, that the government was morally obliged to save their lives, that the officials were duty bound under the Famine Code to give them relief, that they must compel the officials to do so by firmly and loudly invoking the Code, and that they would be perfectly within their legal rights — they would in fact be helping the enforcement of laws —even if they were to refuse to pay the land tax when they were -not in a position to pay it. This was nothing but a rudimentary no-tax campaign and, in spite of Tilak's protestations to the contrary, was understood to be so by the government, which took energetic action against the agents of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, the Sabha itself, and in the end against Tilak himself. The fact that he was arrested in 1897 and sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment on the charge of sedition shows that the farsighted British officialdom was alarmed by the revolutionary potentialities of his campaign among the Deccan peasants in the winter of 1896. Moreover, Tilak himself clearly grasped the deep political implications of his work and drew appropriate political lessons from it. When his lead was not followed by other political workers and the Indian National Congress of 1896 also failed to take any active measures to help or arouse the victims of the famine, he denounced the Congress for its inactivity and wrote in the Kesari, dated 12 January 1897:

For the last twelve years we have been shouting (ourselves) hoarse, desiring that the Government should hear us. But our shouting has no more affected the Government than the sound of a gnat. Our rulers disbelieve our statements or profess to do so. Let us now try to force our grievances into their ears by strong Constitutional means. We must give the best political education possible to the ignorant villagers. We must meet them on terms of equality, teach them their rights and show how to fight constitutionally. Then only will the Government realise that to despise the Congress is to despise the Indian Nation. Then only will the efforts of the Congress leaders be crowned with success. Such a work will require a large body of able and single-minded workers to whom politics would not mean, some holiday recreation but an every-day duty to be performed with strictest regularity and utmost capacity.

He also showed awareness of the historic political role of the peasantry in a country like India. Thus, he declared -

The country's emancipation can only be achieved by removing the clouds of lethargy and indifference which have been hanging over the peasant, who is the soul of India. We must remove these clouds, and for that we must completely identify ourselves with the peasant— we must feel that he is ours and we are his.” [8]

This analysis clearly highlights Tilak’s role as people’s leader. Through his writings, speeches and agitations he was trying to safeguard the economic interests of his fellow countrymen and was trying to sow the seeds of broader unrest which would make the masses the bulwark of the agitation led by the Indian National Congress. Tilak had also expressed the now accepted political-economic theory that the famines are not natural. On the contrary they are manmade disasters. He succinctly writes –

It is meaningless to say that scanty rainfall causes famine. One who has even the rudimentary understanding of the economic principles about how the wealth is provided and distributed would not accept such excuses. (Translation mine)

Then he goes on to write –

Even after ten years of work people don’t have the savings which could sustain them for a year is the root cause of famine. (Translation mine)

He was emphasizing the point that the British political economy was the reason behind people’s lack of purchasing power.

Were Tilak’s endeavours only confrontational and agitational? Certainly not. He was supporting the enterprising Indians to establish an indigenous industry. He was also coaxing Indian workers to look at the international trade unions for inspiration to start unionism here in India. He was writing about the new economic ideas that had come out of Europe and their successful implementation in Asian nations like Japan. He wrote prolifically on economic topics like taxation, industry, trade, tariff, agriculture, labour, poverty, famine etc. The variegated economic topics that Tilak handled in his articles and

editorials are testimony of the importance that he attached to economics. In 1892-93 he wrote simple yet comprehensive and lucid articles on complex topics like the monetary system, exchange rate and silver-gold standards of coinage. They are an example of exemplary economic journalism. As established by noted historian Prof. J. V. Naik, Tilak’s article, written as early as 1883, introduced Karl Marx and his theories to the Indian readers for the first time. Authors have written about the influence of German economist Friedrich List on Justice Ranade’s economic thinking. [1][2][4] But we can find an independent (non-comprehensive) assessment of Listian economics in Indian context even in Lokmanya’s writings.[3]

In 1906 Lokmanya wrote a series of editorials about Irish Sinn Féin movement, its leader Arthur Griffin and economist Friedrich List’s influence on him. It is interesting that he was writing about it when the Swadeshi movement was in full swing. In his Calcutta tour he distributed pamphlets about the Sinn Féin movement.[9] Sinn Féin in Irish language means “We Ourselves”. The title of the article series was Amachech, Pan Kalel Tenva, it loosely translates as “Ours, only if we could understand it”. The first article compares Adam Smith’s economic theory with Friedrich List economic theory. Tilak rejects Adam Smith’s free trade-based economics and favours List’s nationalist economics. He argued that free trade would benefit only the rich nations and poor nations would only remain the source of raw material. At this backdrop he advocated the boycott of British goods and encouraged Swadeshi. Due to this economic foresight, even the ultimate political aim Swarajya wasn’t just about replacing the British bureaucracy with the Indian one, it’s about getting freedom to create national wealth.

The Lokmanya writes –

Swadeshi is God’s mandate. Swarajya doesn’t mean securing the fat salaried jobs, increasing national industry and production to contribute to the national wealth is the real meaning of Swarajya. (Translation mine).

Tilak was the first leader to recognize Maharashtra land’s potential to support the sugar industry. He wrote – “It is not possible for a nation’s financial wellbeing to depend all the time entirely on agriculture”. Thus, he advocated to make agriculture more profitable and to reduce people dependent on agriculture by generating other employment opportunities through industrialization. He walked the talk by supporting crowdfunding initiatives like Paisa Fund and raised capital for indigenous industries. He encouraged small and medium scale industries like matchbox factory, glass factory etc. He notes that post Franco-German war Germany was once again able to prosper due to its policy of raising small and medium enterprises scattered across the country.[10]

Indian labourers’ love for the Lokmanya is an epic saga. He steadfastly supported their cause. In 1896 there were strikes of the guards and signallers of the GIP Railway. British secret report notes that “Mr. Tilak of Poona” is behind these strikes.[11] The 1908 six-day strike by Mumbai millworkers, to show solidarity with Tilak after he was awarded the six-year imprisonment and exile in Mandalay, is an important event in the Indian independence movement. He was acutely aware of the problems of the Indian labourers and the potential of labour unions to participate in the Indian freedom struggle. His political genius lies in the fact that he was able to explain modern economic concepts to the Indian readers/listeners who were on the cusp of modernity, through old cultural idioms, expressions that they understood very well. He used similar methods while explaining trade unionism to the uninitiated Indian workers.

In an editorial titled “Daridrya, Upasmar ani Sampa”, written on 21 August 1906 he says, “Though the old caste system was defective because of other reasons, industrially it was quite effective and alert in safeguarding the interests of a particular trade.”, then he writes, “Trade unions are like our ancient castes. Potter’s or tailor’s birth-based caste has died or would die but caste’s industrial usage won’t diminish. Common trade has become the basis of this new caste like institution.” (Translation mine).

This is how he used the caste idiom to explain modern trade unionism. His English speech before the Madras workers demonstrates the quintessential Tilak style, where he uses the amalgamation of historical reference with the references of present-day scenarios in the world to drive home the point. He says –

Our ancient social and economic system was never designed in favour of the capitalist. Every trade had its own guild. That guild regulated the wages and disputes between the members of the guild, and that state of things is recorded in the books of Manu and Yagnavalkya. It is not a new doctrine; only you have to adopt that doctrine to the changed circumstances of the time. If you organise sufficiently and with a strong will our Indian Government will be compelled to recognise your unions.[12]

In the article, we have seen how Tilak advocated the ideas of a national system of political economy. So, was he then a dyed-in-the-wool economic nationalist? Or was he a closet capitalist as some of his modern day far-left detractors would like us to believe? Tilak fostered friendship with the Labour Party of England. Lenin condemned his Mandalay exile. Tilak praised Lenin’s Bolshevik revolution, but he was also of the opinion that Bolshevism wouldn’t succeed in India. He was the first honorary vice- president of AITUC (All India Trade Union Congress). So, does that mean he was a Marxist-Socialist or would have become one had he lived longer? There cannot be simple answers to these questions. We can venture an educated guess and say he would have been non-dogmatic in his economics as he was in his politics. We would have to probe further into his writings and utterances to understand more about the economic vision of the Lokmanya.

References:

2. Tilak: The Economist by T. V. Parvate

3. समग्र लोकमान्य हिळक, खंड ८, इंग्रजी आहण मराठी अग्रलेख आहण पत्रे, आमचेच - पण कळे ल तेंव्हा - १, २, ३, ४, ५ पान क्र.

५६५-५९५

4. आधुहनक भारत, आचायक शं. द. जावडेकर

5. Empire and the Economist: Analysis of 19th Century Economic Writings in Maharashtra: Neeraj Hatekar Economic and Political Weekly, Feb. 1-7, 2003, Vol. 38, No. 5 (Feb. 1-7, 2003), pp. 469-479

6. गीतारहस्य - बाळ गंगाधर हिळक

7. Lokmanya Tilak – Father of Indian Unrest and Maker of Modern India by D. V. Tamhankar.

8. The Rise and Growth of Economic Nationalism in INDIA – Bipan Chandra

9. लोकमान्य हिळक - धनंजय कीर पान क्र. २६२

10. https://maharashtratimes.com/editorial/samwad/economic-thought-of-the-lokmanya- tilak/articleshow/77156899.cms

11. समग्र लोकमान्य हिळक, खंड ८, इंग्रजी आहण मराठी अग्रलेख आहण पत्रे, पान क्र. 1343

12. समग्र लोकमान्य हिळक, खंड ८, इंग्रजी आहण मराठी अग्रलेख आहण पत्रे, पान क्र. 1320

Soham Thakurdesai studies and analyses Lokmanya Tilak's life, work and philosophy. He has written articles and poems that have been published in various Marathi and English newspapers, magazines and Diwali Ank. 2016 marked the centenary of Lokmanya Tilak's famous clarion call - Home Rule is my birthright and I shall have it. Maharashtra Government published a book of articles written by many eminet Tilak scholars. Soham has contributed an article to the book. He also delivers lectures and speeches on Lokmanya Tilak in Marathi and English.