Documentation by people: towards knowledge society

29 May 2020 15:20:43

It was a unique Women’s Day celebration at Maharashtra’s Rajbhavan. Probably for the first time, a book written by janjati women was published on 8th March 2016. Ho. Governor of Maharashtra published the book. For this programme, these women travelled all the way to Mumbai. Most of them crossed their tehsil boundary for the first time in their life. This book was a compilation of knowledge of these women related to Wild Vegetables. Wild vegetables are an important part of their diet. They have practical knowledge regarding its use. The day was very appropriate for publication as the book literally shows the strength of common women in this country.

We know, you don’t know!

In the development sector we often hear that Indians are poor in documentation. But this is only half-truth and deliberately promoted. Indians may be poor in modern documentation systems especially in written documentation. But we have our own oral systems of documentation. Knowledge generated and transferred orally across India. This knowledge was about everyday living, management of local ecosystems, its utilization, conservation etc. It was also about life in all sense, life beyond humans, what humans need apart from material things etc. It was passed through generations. There was a system to transfer this knowledge through various Utsav’s, Sanskar’s and other specialized programs throughout life.

This knowledge tradition was overlooked in post-independence development philosophy. Few policy makers, scientists, professors and ‘learned’ people used to decide and others used to follow the same. So, we went through the Green Revolution, improved food grain production for some time and lost soil health. We adopted big dams’ creation, displaced lakhs but could not provide water to most of Indians. We provided grains but ended up being malnourished. If we see today’s discourse of development, we discuss how to correct these things.

This thinking has impacted people’s belief to do something for them. So, when I travelled in parts of tribal Andhra Pradesh, I witnessed that people just don’t do anything. They wait for the government ration department to supply food grains and other necessary food items. In Dangs, farmers wait for the government to repair their irrigation lines which can be repaired by themselves. Tribal end up malnourished but do not revive their systems to get good nourishment. ‘We know and you don’t know’ approach has ended up making the community disabled.

On other hands, global systems changed in last 200-300 years due to Industrial, IT and such other revolutions. Knowledge has become a lot more important than material wealth in today’s world. Overall knowledge piracy and use of such knowledge for profits has become a new common. It is true in areas like medicine. So, we also need to become more vigilant. We need to adopt new information storage systems at local, national level. We need to cultivate knowledge, pass it on to next generation and also need to store using modern systems.

Changed circumstances, revising systems, but what about People?

Few scientists and policy makers realized this. It was in 2001, first law was enacted which provided some recognition to farmers and communities who developed/ preserved local crop varieties. In 2002, in a landmark Biodiversity law, documentation of local biodiversity and associated knowledge by the community became an important document in local development process. Similarly, many more laws recognized local knowledge and the need of its documentation.

These laws created management systems from local to national level. Let’s take example of the Biodiversity Act 2002. Under this act, National Biodiversity Authority, State Biodiversity Boards and Biodiversity committees at District, Tehsil and Panchayat levels were formed. Panchayat levels committees are responsible for documentation of local biodiversity and associated knowledge. People’s Biodiversity Registers formats and manuals on how to make documents were prepared. Similarly, one can see formats for documentation of crop varieties under PPVFRA. The Watershed programmes involves PRA techniques to get to know what people want, there are climate resilient committees to document people’s experience and knowledge about climate change and what not. People’s knowledge became a buzz word in development. But what about people? Are these laws, manuals and formats sufficient to motivate them, take action, promote documentation?

People who were dumped as just beneficiaries in the development process for 40-50 years cannot just get involved using manuals, formats. They need something more than this. Something very Indian. What could be this? The answer lies in our own system of knowledge transfer. We had a grand Navratri programme all over India. A common thing everywhere is sowing of seeds for 9 days. It is actually a seed testing programme associated with worship of Goddess. People gather, discuss about rains, seeds, share experiences through songs etc. Seed tests are shared with others. Seed pooja festivals happened before monsoon and rabbi season. In parts of Central India, mahua, chironji harvest starts after common van poojan. There are community gathering and programmes for almost every activity people undertake for living.

Reviving traditions as knowledge generators

An experiment in Kanjala Village, Akkalkuwa tehsil Nandurbar has thus become an important example. YOJAK and Ekalvya Gramin Adivasi Vikas Sanstha were promoting biodiversity documentation in this area. When biodiversity documentation using formats was started in 2014, it became somewhat a writing exercise. Soon participation reduced. So, after churning for a few months, an experiment was planned. A Wild Vegetable festival was announced in the village. This was especially for women. Women should bring wild vegetables as well as its cooked recipe. People decided the day in the last week of August for the programme. Wild vegetables are in abundance during August end and September as per their observations. In the first year, about 20 women participated with 20-25 vegetables. They shared their information about the plant, its habitat, habit etc.

Also, they shared its use – as vegetable and medicine, how to cook it and precautions one should take. It was a programme where people themselves were talking about their wealth. The interesting part was women were talking and men, children were listening carefully. This program is now happening every year and in the last 5-6 years more than 90 plant species were documented locally. The book referred to in the beginning was a product of this process. Festival evolved over the years and a day-long programme consisting of traditional music, special pooja, display of plants and recipes, its documentation, involving outside villagers and schools started.

In 2019, the process was upscaled at district level. People’s organizations from different parts of Nandurbar, NGOs and District biodiversity committee with support from Tribal department and YOJAK organized 1st district level Wild Vegetable Festival. It was a grand success and resulted in a document on Wild Vegetables of Nandurbar District.

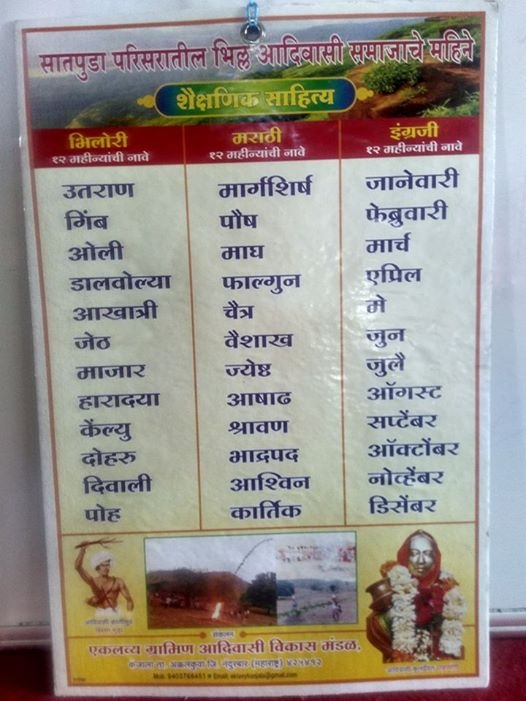

A simple process at village level has resulted into very basic and necessary documentation. During the process, an interesting case emerged. After festival, detailed documentation of each species were conducted in small groups. Women were not very comfortable when asked to link English calendar months with vegetables. They were not able link vegetable occurrence with these months. When we enquired further, their Bhili language calendar emerged which they can link easily. It helped to develop a calendar linking Bhili, Marathi and English months. This was something very new and unique for the area. First time bhili calendar was brought on paper. This has also eased documentation process.

Such documentation process helps in multiple ways. As community forest rights under FRA 2006 started, the data generated and published book came handy in showing people’s dependence and use of local forest. Next step of documentation followed to understand the availability of Mahua, Custard apple in the area. It helped to set up small trade units of the same. First time people sold custard apple in major markets and benefitted. Similarly, the data was useful for making Van Dhan Kendra proposal submitted by village to Government for NTFP trade.

This experiment gave us confidence to convert documentation exercise into something that people will understand and accept. YOJAK developed 4 such programmes for Seeds, Forest (NTFP), Water and Youths. A manual to conduct the festivals, what to document, how to prepare for this, who should participate, who should talk and who should not, whom to involve for scientific documentation, forming youth teams in villages for post programme documentation etc was developed. These 5 festivals were then tested in 9 states across central India in 18 tribal clusters involving more than 100 villages. Everywhere the concept was accepted and evolved into its own unique way. Each festival is linked with local harvesting, sowing months. These set of programmes can help to initiate documentation by truly involving people on ground.

Knowledge generation: Sewa for Antyodaya

Similarly, we need to develop new systems for village level documentation. Jaldoot, an experiment to document rainfall at village level was started in 2008 in 8 villages on the banks of river Nesu, Navapur, Nandurbar district. Village community has decided a volunteer who can keep records of village data. This is kind of sewa for the village by the person. The process after ups and downs is now settled and excellent data is generated by these jaldoot. The data was very useful to get financial assistance from the government when villages experienced hailstorm in January 2014 but were not included in government list. This data recording is now linked with the GSDA record of rainfall.

Path of antyodaya considers knowledge and traditions as two sides of a coin. India always linked knowledge with traditions to involve every single person in society. During the last few decades, knowledge traditions became rituals due to various reasons. It is necessary to revisit traditions and revive science, knowledge associated with the same. Knowledge documentation and transfer to new generation at grassroot level will make last person part of knowledge society and lead to antyodaya.