Language-dialect dichotomy.. a 'knotty' problem!?

Total Views |

Is Urdu a dialect of Hindi? Or is it a separate language? Why is Konkani in Goa an independent language and Konkani in the Konkan a dialect of Marathi? Why are the Tani group of speech varieties in Arunachal Pradesh treated as dialects when the speakers of these varieties do not understand each other? The language-dialect dichotomy is a knotty problem: social, political and even psychological factors decide the status of a speech variety. The distinction is rarely made using linguistic criteria.

Language changes all the time. It changes through time, from one generation to another even within a single family. It varies from one region to another and from one social group to another. These are called dialects. Let’s begin our exploration of dialects and their study by first understanding the relationship between language and dialect.

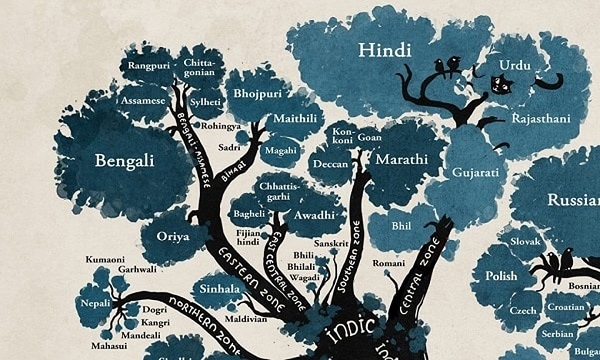

Is Urdu a dialect of Hindi? Or is it a separate language? Why is Konkani in Goa an independent language and Konkani in the Konkan a dialect of Marathi? Why are the Tani group of speech varieties (e.g. Apatani, Adi, Galo, Mising, Nyishi, etc.) in Arunachal Pradesh treated as dialects when the speakers of these varieties do not understand each other? The language-dialect dichotomy is a knotty problem: social, political and even psychological factors decide the status of a speech variety. The distinction is rarely made using linguistic criteria. Urdu has a Persianised vocabulary and is written in the Perso-Arabic script; Hindi, on the other hand, has a Sanskritised vocabulary and is written in the Devanagari script. Speakers of each language find the other intelligible. Yet, the two are recognised as independent languages by the Indian constitution. More recently, the two languages have come to represent two distinct socio-religious identities: Hindi - Hindu and Urdu - Muslim. Traditionally considered a dialect of Marathi, Goan Konkani was given official recognition in 1992 following agitations in Goa. Members of the Tani group in Arunachal Pradesh, on the other hand, assert their shared ethnic identity by considering their mutually unintelligible speech varieties as dialects of a single language.

A language is often equated with its standard variety. When second language learners learn Hindi, for example, they learn the standard variety of the language, not one of its dialects like Awadhi, Bhojpuri or Chhattisgarhi. So, how does the ‘standard variety’ come into being? Very often, a speech variety of a prestigious group of people is promoted to the status of the standard. These people are regarded to be prestigious because they are educated or they have economic power or for some such non-linguistic asset. As the English playwright, G.B. Shaw famously said, a language is a dialect with an army and a navy! Once a particular dialect is selected to represent the language, its grammar is formally codified and documented; its vocabulary is also documented in the form of dictionaries; its spelling is also formally decided by language academies.

Speakers associate qualities such as ‘refined’, ‘logical’ and ‘melodious’ with the standard speech variety; they assign attributes such as ‘greater intelligence’ and ‘reliability’ with the speakers of the standard variety. Qualities such as ‘uncouth’, ‘uneducated’, ‘rough’ are often associated with non-standard dialects. It is important to realise that these are subjective assessments of particular speech varieties and their speakers. Linguistically neither the language nor the dialect is superior or inferior. Dr. N.G. Kalelkar, a Marathi linguist, gave these examples to illustrate this arbitrariness: while राणी is considered the standard (i.e. correct) pronunciation and रानी the non-standard pronunciation of the same word in Marathi, रानी is the correct and standard pronunciation of the word in the country’s official language,

Hindi. Kalelkar gives a second example: the pronunciation होता and नव्हता are both standard, but व्हता is considered non-standard, uneducated pronunciation in Marathi. Speakers of non-standard dialects imbibe others’ attitudes towards their own speech. They are often apologetic about their speech – it is rustic, has no grammar, no script. It must be noted that, in principle, a dialect or a language can be written in any script (maybe with a few modifications). Konkani, for example, is written in Devanagari, Roman, Perso-Arabic, Malayalam and Kannada scripts. Further, if grammar is a set of rules for forming words from sounds and sentences from words, dialects have grammars too! For example, सुंदर फूल, बडा घर, तेज रफ्तार are acceptable combinations in standard Hindi, where the modifiers (adjectives) सुंदर, बडा and तेज precede the nouns फूल, घर and रफ्तार. However, *फूल सुंदर, *घर बडा, *रफ्तार तेज are unacceptable combinations (e.g. *मैने फूल सुंदर देखा is unacceptable).

Similarly, लडका गाडी तेज बहुत चलाता हे is unacceptable in Hindi where the modifier word बहुत follows the modified word तेज. This is also the rule in dialects of Hindi: the modifier word precedes the modified word. Speech varieties have ‘rules’ of pronunciation too: शादी of standard Hindi is pronounced as सादी in some dialects of Hindi, not because speakers of the dialect are lazy, but because the dialect has only the स sound. While the consonant sequences ‘bl’ and ‘pr’ occur in English loan words in standard Hindi as in ‘उसका ब्लड प्रेशर बढ गया’ the same consonant sequences are broken as in ‘बिलड पिरेसर’ in dialects which do not allow such consonant sequences. Recall the joke about the man from UP who ridiculed the man from Haryana who pronounced the word ‘station’ as सटेशन instead of pronouncing it correctly as इस्टेशन!

The standard dialect of a language has multiple functions: it is used in administration, formal education, mass media, etc. However, non-standard dialects are primarily used only in informal conversation. The reach of the standard increases as access to formal education increases; the standard begins to gradually displace regional and social dialects. Dialectal differences begin to get ‘levelled out’. With the spread of education, younger generations begin to attach greater value to the standard dialect; at times they are even embarrassed by their home dialect. Educated persons realise that the standard language is a gateway to opportunities for employment and economic uplift. Such a change in attitude accelerates the shift from dialect to standard.

Any speech variety is a storehouse of the accumulated wisdom of its speakers over generations. Both the vocabulary and the grammar of the speech variety are representations of the distinctive worldview shared by the speakers of the language. The names of flora, fauna, body parts, kinship terms, cooking processes, bodily functions, rituals, etc. are stored in the language. When a dialect / language disappears, this storehouse of information disappears with it. Language is an intangible resource for studying our own cultural wisdom, history and cognition. Documentation of dialects and less-prestigious languages has therefore become an urgent need today.