Saturn is losing its intrigued rings at ‘worst case scenario’ rate

Greenbelt, Maryland, Dec 18: New NASA research confirms that, Saturn is losing its iconic rings at the maximum rate estimated from Voyager 1 and 2 observations made decades ago.

The rings are being pulled into Saturn by gravity as a dusty rain of ice particles under the influence of Saturn’s magnetic field.

“We estimated that, ‘ring rain’ drains an amount of water products that could fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool from Saturn’s rings in half an hour”, said James O’ Donoghue of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

“From this alone, the entire ring system will be gone in 300 million years, but add to this the ‘Cassini’ spacecraft measured ring-material detected falling into Saturn’s equator, and the rings have less than 100 million years to live, this is relatively short, compared to Saturn’s age of over four billion years’’, O’ Donoghue said.

“We are lucky to be around to see Saturn’s ring system, which appears to be in the middle of its lifetime. However, if rings are temporary, perhaps we just missed out on seeing giant ring systems of Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, which have only thin ringlets today!” O’Donoghue added.

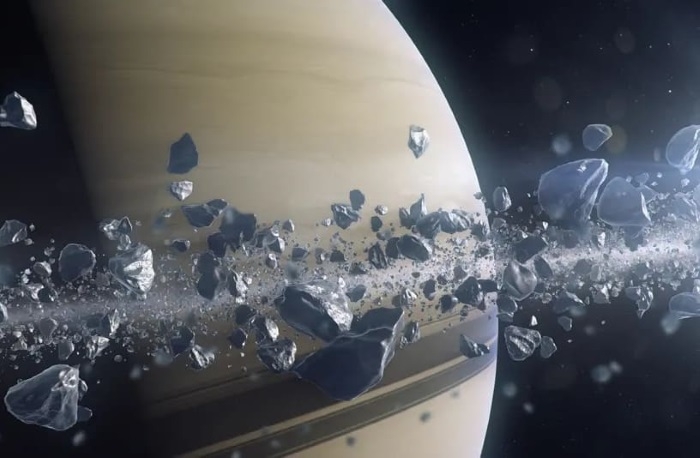

Various theories have been proposed for the ring’s origin. If the planet got them later in life, the rings could have formed when small, icy moons in orbit around Saturn collided, perhaps because their orbits were perturbed by a gravitational tug from a passing asteroid or comet.

The first hints that ring rain existed came from Voyager observations of seemingly unrelated phenomena: peculiar variations in Saturn’s electrically charged upper atmosphere (ionosphere), density variations in Saturn’s rings, and a trio of narrow dark bands encircling the planet at northern mid-latitudes. These dark bands appeared in images of Saturn’s hazy upper atmosphere (stratosphere) made by NASA’s Voyager 2 mission in 1981.

Saturn’s rings are mostly chunks of water ice ranging in size from microscopic dust grains to boulders several yards (meters) across. Ring particles are caught in a balancing act between the pull of Saturn’s gravity, which wants to draw them back into the planet, and their orbital velocity, which wants to fling them outward into space.

Tiny particles can get electrically charged by ultraviolet light from the Sun or by plasma clouds emanating from micrometeoroid bombardment of the rings. When this happens, the particles can feel the pull of Saturn’s magnetic field, which curves inward toward the planet at Saturn’s rings.

In some parts of the rings, once charged, the balance of forces on these tiny particles changes dramatically, and Saturn’s gravity pulls them in along the magnetic field lines into the upper atmosphere.

The team also discovered a glowing band at a higher latitude in the southern hemisphere. This is where Saturn’s magnetic field intersects the orbit of Enceladus, a geologically active moon that is shooting geysers of water ice into space, indicating that some of those particles are raining onto Saturn as well.

“That wasn’t a complete surprise,” said Connerney. “We identified Enceladus and the E-ring as a copious source of water as well, based on another narrow dark band in that old Voyager image.”

The geysers, first observed by Cassini instruments in 2005, are thought to be coming from an ocean of liquid water beneath the frozen surface of the tiny moon. Its geologic activity and water ocean make Enceladus one of the most promising places to search for extraterrestrial life.