APFRA, a Law Christian Groups Fear in Arunachal—And Desperately Want to Stop

Total Views |

Arunachal Pradesh, once a stronghold of diverse indigenous faiths, is undergoing an alarming demographic shift. Christianity, which was a mere 0.79% in 1971, has now surged to a staggering 30%, while the (region’s) native religions continue to decline. After 46 years of dormancy, the Arunachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1978, (APFRA) is set to be implemented. This legislation has become the focal point of debate in the state. Originally passed by the first assembly of the then Union Territory of Arunachal Pradesh in 1978, the law received Presidential assent but remained unimplemented for 46 years due to consistent resistance from Christian leaders.

Following the Gauhati High Court’s directive to the government last September to finalise the draft for its implementation within six months, the move has sparked strong opposition from Christian organisations, particularly the Arunachal Christian Forum (ACF). Notably, the Forum was formed a year after the law was passed and has been at the forefront in resisting its enforcement.

While the ACF is intensifying its campaign and staging hunger strikes, indigenous faith organisations such as Indigenous Faiths and Cultural Society of Arunachal Pradesh (IFCSAP) are rallying in support of the Act, arguing that it is crucial for preserving tribal culture, traditions, and belief systems, which have been eroding due to Christian missionary activities. They assert that rising religious conversions threaten the identity and existence of indigenous communities, and that the Act will help safeguard their way of life by preventing conversions through inducement or fraudulent means.

During the 1950s, Arunachal Pradesh, then known as the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), was undergoing drastic socio-cultural changes, posing a threat to its indigenous fabric. At that time, Christian missionaries were barred from entering NEFA, but this restriction did not stop the missionaries from carrying out their “activities”. Instead, they looked for other ways to spread their influence. They focused on the foothill areas of Assam. This later helped them enter NEFA.

Church-backed schools and healthcare clinics were established in areas bordering Arunachal within Assam. These institutions catered largely to tribal students and the poor living along the border, providing education and medical aid. However, these centers also became avenues for religious indoctrination, gradually leading to conversions.

The slow and steady expansion of Christian missions in the foothills of Assam soon bore results. By 1957, the first church in Arunachal Pradesh was built in Rayang village, East Siang district, near Assam’s Dhemaji district. This marked the beginning of a significant religious shift in the region. In the 1971 Census, Christians made up just 0.79% of Arunachal’s population. By 1981, their numbers had risen sharply to 4.32%.

Sociologists Bhaswati Borgohain and Mekory Dodum, in their 2023 study titled “Religious Nationalism, Christianisation, and Institutionalisation of Indigenous Faiths in Contemporary Arunachal Pradesh, India”, highlighted, “This change was massive in specific communities located nearer the foothill missions such as the Padam, Adi, Nocte and Nyishi…..debates about the various ways in which missionaries proselytise, the socio-cultural changes that conversion brought to the respective tribes, and what level of threat conversion poses to indigenous religions” in the state Assembly, with members demanding “the protection of their indigenous religions and cultures”.

Owing to the sudden and visible changes, the Arunachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act (APFRA) – the first such law in the region – had been passed by the first Assembly of the then Union Territory of Arunachal Pradesh and received Presidential assent in 1978. However, it remained in cold storage for 46 years as Christian leaders opposed it. It would have remained unimplemented had it not been for the Guwahati High Court. In 2022, advocate Tambo Tamin, a former general secretary of the IFCSAP, filed a petition seeking judicial intervention in the state’s failure to frame rules that will put the 1978 Act into effect.

It prohibits religious conversion “by use of force or inducement or by fraudulent means” and entails punishment of imprisonment for up to two years, and a fine of up to Rs. 10,000 for the offence of “converting or attempting to convert” forcefully “from one religious faith to another faith.” The Act also requires that every act of conversion be reported to the Deputy Commissioner of the district concerned. Failure to report a conversion invites punishment for the person conducting the conversion as well.

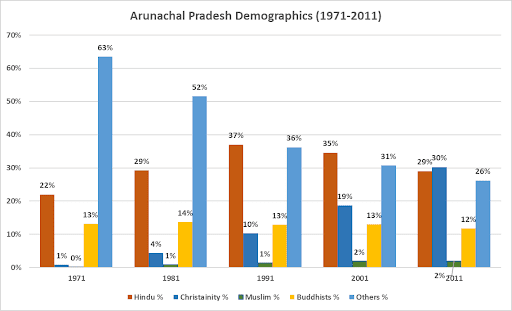

The Act specifies that “religious faiths” in this context include “indigenous” faiths, which the Act defines as religions, beliefs, observances, customs, etc. “as have been found sanctioned, approved, performed by the indigenous communities of Arunachal Pradesh from the time these communities have been known…” Included in this definition is Buddhism as practised among the Monpas, Membas, Sherdukpens, Khambas, Khamptis and Singphos; nature worship including the worship of Donyi-Polo among communities in the state; and Vaishnavism in practised by the Noctes and Akas. The Table 1 shows that

So, why so much opposition when the Act is not meant to counter any religion but to conserve the rich indigenous cultural heritage of the state?

Arunachal Pradesh and Other North-East states Data

Table 1 illustrates a dramatic rise in Christianity, increasing from 0.79% in 1971 to 30% in 2011. In contrast, the proportion of people following other religions (mainly Donyi Polo) has sharply declined, dropping from 63% in 1971 to 26% in 2011. This highlights the exponential growth of Christianity, driven by aggressive evangelism over the past few decades, which has significantly impacted the indigenous faiths and cultures of the Himalayan state. There is concern that the next census will show the Christian population in the state surpassing 40%.

Source: Vayuveg

The Opposition to the Act has extended beyond Arunachal Pradesh, drawing resistance from Christian groups across the Northeast. The region includes Christian-majority states like Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Mizoram, while Manipur also has a significant Christian population.

An analysis of religious demographics in the Northeast—excluding Arunachal Pradesh — reveals a notable shift over time. The data indicates a decline in the Hindu population, while Christianity and Islam have seen steady growth. The most concerning trend, however, is the sharp decline in the "Others" category, which represents indigenous faiths. This decline has been particularly pronounced in states like Meghalaya and Nagaland, raising concerns about the rapid erosion of indigenous belief systems in the region.

And if we see the demographics of all the north-eastern states, it reveals a notable shift. It is a decline in the Hindu population over the decades, while Christianity and Islam have shown consistent growth. In 1991, Hindus made up 61% of the population, which dropped to 57% in 2001 and further declined to 54% in 2011. On the other hand, Christianity increased from 13% in 1991 to 16% in 2001, and then to 17% in 2011. The Muslim population has also witnessed significant growth, rising from 22% in 1991 to 23% in 2001, and further to 25% in 2011.

All the graphs has been sourced by Vayuveg

This shift highlights the gradual erosion of the Hindu demographic in the region while Christianity and Islam continue to expand. If this trend persists, it could lead to cultural and socio-political transformations, especially in states where indigenous faiths and traditions have historically played a dominant role.

The sharp rise in Christianity in Arunachal Pradesh underscores the aggressive missionary activities that have reshaped the state's religious landscape. As a result, the urgency to implement the Act has become more critical with indigenous faiths witnessing a drastic decline. Though the damage has already been done, the Act stands as a necessary measure to curb further conversions through inducement or coercion and to protect the cultural and religious heritage of the indigenous communities.

The intense opposition from Christian groups — not just in Arunachal but across the North-East — reveals a deeper fear among missionaries of losing the unchecked influence they have long exercised in the region.

Following the Gauhati High Court’s directive to the government last September to finalise the draft for its implementation within six months, the move has sparked strong opposition from Christian organisations, particularly the Arunachal Christian Forum (ACF). Notably, the Forum was formed a year after the law was passed and has been at the forefront in resisting its enforcement.

While the ACF is intensifying its campaign and staging hunger strikes, indigenous faith organisations such as Indigenous Faiths and Cultural Society of Arunachal Pradesh (IFCSAP) are rallying in support of the Act, arguing that it is crucial for preserving tribal culture, traditions, and belief systems, which have been eroding due to Christian missionary activities. They assert that rising religious conversions threaten the identity and existence of indigenous communities, and that the Act will help safeguard their way of life by preventing conversions through inducement or fraudulent means.

Why was it introduced?

During the 1950s, Arunachal Pradesh, then known as the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), was undergoing drastic socio-cultural changes, posing a threat to its indigenous fabric. At that time, Christian missionaries were barred from entering NEFA, but this restriction did not stop the missionaries from carrying out their “activities”. Instead, they looked for other ways to spread their influence. They focused on the foothill areas of Assam. This later helped them enter NEFA.

Church-backed schools and healthcare clinics were established in areas bordering Arunachal within Assam. These institutions catered largely to tribal students and the poor living along the border, providing education and medical aid. However, these centers also became avenues for religious indoctrination, gradually leading to conversions.

The slow and steady expansion of Christian missions in the foothills of Assam soon bore results. By 1957, the first church in Arunachal Pradesh was built in Rayang village, East Siang district, near Assam’s Dhemaji district. This marked the beginning of a significant religious shift in the region. In the 1971 Census, Christians made up just 0.79% of Arunachal’s population. By 1981, their numbers had risen sharply to 4.32%.

Sociologists Bhaswati Borgohain and Mekory Dodum, in their 2023 study titled “Religious Nationalism, Christianisation, and Institutionalisation of Indigenous Faiths in Contemporary Arunachal Pradesh, India”, highlighted, “This change was massive in specific communities located nearer the foothill missions such as the Padam, Adi, Nocte and Nyishi…..debates about the various ways in which missionaries proselytise, the socio-cultural changes that conversion brought to the respective tribes, and what level of threat conversion poses to indigenous religions” in the state Assembly, with members demanding “the protection of their indigenous religions and cultures”.

What is APFRA?

Owing to the sudden and visible changes, the Arunachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act (APFRA) – the first such law in the region – had been passed by the first Assembly of the then Union Territory of Arunachal Pradesh and received Presidential assent in 1978. However, it remained in cold storage for 46 years as Christian leaders opposed it. It would have remained unimplemented had it not been for the Guwahati High Court. In 2022, advocate Tambo Tamin, a former general secretary of the IFCSAP, filed a petition seeking judicial intervention in the state’s failure to frame rules that will put the 1978 Act into effect.

It prohibits religious conversion “by use of force or inducement or by fraudulent means” and entails punishment of imprisonment for up to two years, and a fine of up to Rs. 10,000 for the offence of “converting or attempting to convert” forcefully “from one religious faith to another faith.” The Act also requires that every act of conversion be reported to the Deputy Commissioner of the district concerned. Failure to report a conversion invites punishment for the person conducting the conversion as well.

The Act specifies that “religious faiths” in this context include “indigenous” faiths, which the Act defines as religions, beliefs, observances, customs, etc. “as have been found sanctioned, approved, performed by the indigenous communities of Arunachal Pradesh from the time these communities have been known…” Included in this definition is Buddhism as practised among the Monpas, Membas, Sherdukpens, Khambas, Khamptis and Singphos; nature worship including the worship of Donyi-Polo among communities in the state; and Vaishnavism in practised by the Noctes and Akas. The Table 1 shows that

So, why so much opposition when the Act is not meant to counter any religion but to conserve the rich indigenous cultural heritage of the state?

Arunachal Pradesh and Other North-East states Data

Table 1 illustrates a dramatic rise in Christianity, increasing from 0.79% in 1971 to 30% in 2011. In contrast, the proportion of people following other religions (mainly Donyi Polo) has sharply declined, dropping from 63% in 1971 to 26% in 2011. This highlights the exponential growth of Christianity, driven by aggressive evangelism over the past few decades, which has significantly impacted the indigenous faiths and cultures of the Himalayan state. There is concern that the next census will show the Christian population in the state surpassing 40%.

Source: Vayuveg

The Opposition to the Act has extended beyond Arunachal Pradesh, drawing resistance from Christian groups across the Northeast. The region includes Christian-majority states like Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Mizoram, while Manipur also has a significant Christian population.

An analysis of religious demographics in the Northeast—excluding Arunachal Pradesh — reveals a notable shift over time. The data indicates a decline in the Hindu population, while Christianity and Islam have seen steady growth. The most concerning trend, however, is the sharp decline in the "Others" category, which represents indigenous faiths. This decline has been particularly pronounced in states like Meghalaya and Nagaland, raising concerns about the rapid erosion of indigenous belief systems in the region.

And if we see the demographics of all the north-eastern states, it reveals a notable shift. It is a decline in the Hindu population over the decades, while Christianity and Islam have shown consistent growth. In 1991, Hindus made up 61% of the population, which dropped to 57% in 2001 and further declined to 54% in 2011. On the other hand, Christianity increased from 13% in 1991 to 16% in 2001, and then to 17% in 2011. The Muslim population has also witnessed significant growth, rising from 22% in 1991 to 23% in 2001, and further to 25% in 2011.

*Data about Assam of the 1981 census was not available

All the graphs has been sourced by Vayuveg

This shift highlights the gradual erosion of the Hindu demographic in the region while Christianity and Islam continue to expand. If this trend persists, it could lead to cultural and socio-political transformations, especially in states where indigenous faiths and traditions have historically played a dominant role.

The sharp rise in Christianity in Arunachal Pradesh underscores the aggressive missionary activities that have reshaped the state's religious landscape. As a result, the urgency to implement the Act has become more critical with indigenous faiths witnessing a drastic decline. Though the damage has already been done, the Act stands as a necessary measure to curb further conversions through inducement or coercion and to protect the cultural and religious heritage of the indigenous communities.

The intense opposition from Christian groups — not just in Arunachal but across the North-East — reveals a deeper fear among missionaries of losing the unchecked influence they have long exercised in the region.