Price that Hindus Paid for a Zero …?

On the occasion of National Science Day, let us delve into this lesser-known chapter in the global dissemination of the concept of zero.

Total Views | 613

Although Aryabhatta laid the foundation for the decimal system and introduced the concept of zero and Brahmagupta provided a clear explanation of it, the Western world is believed to have received this knowledge through the Arabs. But how did this knowledge of zero reach the Arabs?

Some suggest that trade relations between the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Peninsula facilitated the exchange of knowledge. However, a detailed analysis of historical records reveals inconsistencies in this assumption.

The truth is that this knowledge was transmitted to the Abbasids through the Barmakids from Kashyap Maru, referring to present-day Kashmir, where it was originally developed under the guidance of the sage Kashyapa. However, it did not reach them effortlessly.

It may seem controversial to state that the Abbasids engaged in jihad to acquire this knowledge, but this little-known historical fact holds significance. On the occasion of National Science Day, let us delve into this lesser-known chapter in the global dissemination of the concept of zero.

In the Balkh region—stretching from present-day Kashmir to Afghanistan—a sect known as the Barmakids once thrived. The Barmakids were an influential intellectual class in early centuries, originally adherents of Buddhist philosophy. Their deep engagement with Buddhist teachings made them well-versed in disciplines such as mathematics, astronomy, and geography. Additionally, they possessed knowledge of Sanskrit, a language that was rare outside India.

However, with the expansion of the Umayyad military and their jihadist campaigns, the Barmakids were compelled to convert to Islam. Recognizing their vast knowledge, the Abbasid Caliphate granted them key administrative roles and tasked them with translating crucial Sanskrit scientific texts into Arabic. Once these translations were completed, much of the original Sanskrit literature was deliberately destroyed. As a result, the foundational knowledge of these sciences came to be regarded as Arab contributions in the Western world.

This is not merely a legend but a historical reality. In the following sections, we will examine these events in detail.

Before moving on to the core topic, let us first explore the history of zero.

The History of Zero: Tracing Its Origins

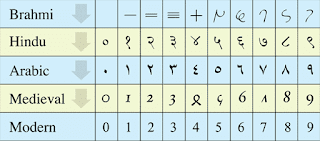

Research has revealed that while the exact origin and inventor of zero remains uncertain, there is global consensus that the concept of zero was first developed in India. Some accounts suggest that the Babylonians were the first to use a form of zero, followed by the Mayan civilization. However, these early representations had no significant impact on numerical systems. It was only in the mid-5th century that zero was systematically rediscovered and integrated into mathematics in India.

One of the earliest known mathematical documents from the Indian subcontinent is the Bakhshali Manuscript, discovered in 1881 near Peshawar, Pakistan. Although its exact date remains undetermined, this manuscript contains a symbolic representation of zero.

Many scholars consider the discovery of zero and the development of the decimal system to be among ancient India’s most profound contributions to human civilization. The decimal system, based on nine digits and a symbol for zero, follows a place-value notation that allows for precise numerical representation. This system can be traced back to the Vedas and even the Valmiki Ramayana.

Excavations at sites of the Indus-Sarasvati civilization, including Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro (dating back to around 3000 BCE), suggest the use of a mathematical system that likely influenced later developments. The earliest known written record explicitly demonstrating the decimal place-value system and zero is found in the Jain text Lokavibhaga, composed in 458 CE. This text employs Sanskrit numerical terms, providing a structured approach to mathematical notation.

The first concrete evidence of distinct numerical symbols for decimal digits, including a small circular dot representing zero, appears in an inscription from 876 CE at the Chaturbhuj Temple in Gwalior. While some copper plates from the 6th century also feature small ‘o’ symbols, their identification as zero remains debatable.

These historical findings highlight India's pivotal role in shaping modern numerical systems, laying the foundation for mathematical advancements worldwide.

The Origins of the Barmakids

According to several Arab historians, the Barmak lineage traces back to Iran, where they were originally high priests of the grand fire temple in Nau Bahar, near Balkh. The historian Al-Masudi, in his work Muruj adh-Dhahab, describes the Barmaks as Magians (Zoroastrian priests) and the chief custodians of this revered fire temple. He further notes that rulers of the region treated them with great respect, entrusting them with the complete management of temple wealth and donations. The title Barmak was used to refer to the head of this religious institution, which later evolved into the family name Barmakid (or Barmaki), as seen in figures like Khalid ibn Barmak, a prominent administrator under the Abbasid Caliphate.

However, recent research challenges this traditional view, suggesting that the Barmakids were not of Iranian origin but had strong connections to northern India, particularly Kashmir. Professor Zabihullah Safavi of Tehran University presents this argument in his seminal work The Barmakids, asserting that their roots lay in the Indian subcontinent. Similarly, historian Syed Sulaiman (in Arab-o-Hind ke Talluqat, 1930) strongly argues that Nau Bahar was not a Zoroastrian fire temple but rather a Buddhist monastery. This view is further supported by W. Barthold, a noted scholar of Central Asian history, who also identifies Nau Bahar as a significant Buddhist vihara.

Renowned scholar R. S. Pandit goes even further, claiming that the term Barmak itself has Indian origins. He highlights that despite their conversion to Islam, contemporary sources suggest that the Barmakid family was never fully accepted as devout Muslims. This skepticism is recorded in Ibn al-Nadim’s Al-Fihrist, which mentions doubts about their religious allegiance.

Despite their shifting religious identity, the Barmakids played a crucial role in the intellectual exchanges between India and the Abbasid Caliphate. They invited Hindu scholars to Baghdad, appointing them as chief physicians in their hospitals and commissioning translations of key Sanskrit texts into Arabic. These translations covered subjects such as medicine, toxicology, and philosophy, ensuring that Indian knowledge systems influenced the Islamic and, later, the Western world.

The Origin of the Word ‘Barmak’

According to Professor C. S. Upasak (author of The History of Buddhism in Afghanistan), the term Barmak is derived from the Sanskrit word Vara-Aramik, which translates to chief administrator of a Buddhist monastery. The word Aramik refers to an official responsible for overseeing the maintenance and management of a Vihara (Buddhist monastery), including the supervision of its wealth and resources, under the authority of the Buddhist monastic order.

The Nava Vihara monastery, which played a central role in this system, owned approximately 1,500 square kilometers of land. To manage this vast estate, multiple Aramik officials were appointed, with the head of these administrators being designated as the Vara-Aramik. This title eventually evolved into Barmak, which became a hereditary designation for the powerful Barmakid family in later centuries.

The Kashmiri Origins of the Barmakids and Their Conversion to Islam

In the 1st century CE, following the great Buddhist council convened by the Kushan emperor Kanishka, the Tokharian monk Ghoshaka returned to Balkh and established the Western Vaibhashika tradition. This philosophical school was an offshoot of the Sarvastivada sect, which had flourished in Kashmir. The monastery founded by Ghoshaka, known as Nava Vihara, soon became a prestigious center of Buddhist learning along the Silk Road.

For centuries, Nava Vihara remained under the leadership of a hereditary priestly family, believed to be of Kashmiri origin. The heads of this lineage were referred to as Barmak, a title derived from the local pronunciation of their position as chief administrators of the monastery.

One of the later Barmaks was the chief high priest of Nava Vihara. In 708 CE, when the Turk Shahis regained power in the region, they executed this high priest, who had recently converted to Islam. However, before this tragedy, his only surviving child had already been sent to Kashmir with his mother. In Kashmir, this descendant of the Barmak lineage studied astrology, medicine, and philosophy.

In 715 CE, the Umayyad army launched a decisive conquest of Balkh, leading to the catastrophic destruction of Nava Vihara. To survive, it is believed that the Barmak and his family converted to Islam and subsequently integrated into the Umayyad court. Due to his expertise in medicine, he gained significant recognition, and his astrological knowledge further enhanced his family's influence. According to historical accounts, he is credited with predicting the Abbasid victory in 745 CE, which further cemented the family's prominence in the Islamic world.

Contributions of the Later Generations of the Barmakid Family

Khalid ibn Barmak, the son of Barmak, played a crucial role in the early Abbasid Caliphate, holding key administrative positions under the first two Abbasid caliphs. His family grew extremely close to the ruling dynasty, becoming one of the most influential households in the empire. Khalid’s son, Yahya ibn Barmak, served as the tutor to the young Harun al-Rashid and later became his vizier (prime minister).

Yahya’s two sons, Abu-Fadl and Ja’far, also secured high-ranking positions in the Abbasid administration. The legendary vizier Ja’far ibn Yahya, frequently mentioned in The Arabian Nights, was none other than this Barmakid noble. However, in 803 CE, the family's fortunes took a dramatic downfall—possibly due to Ja’far’s alleged relationship with Abbasah, the sister of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Before their downfall, however, the Barmakids were regarded as the most powerful family in Baghdad, second only to the caliph himself.

Yahya ibn Barmak’s legacy extended beyond politics—he was instrumental in translating Sanskrit texts on astronomy, philosophy, and medicine into Arabic, highlighting the scholarly tradition of his lineage. He also dispatched envoys to gather extensive knowledge about India and invited a large number of Ayurvedic scholars from Sindh and Kashmir to Baghdad, further fostering cultural and scientific exchanges between India and the Islamic world.

The Ultimate Act of Cultural Appropriation

The great libraries and translation centers of Baghdad remained active until the Mongols sacked the city in 1258 CE. It is said that thousands of manuscripts were thrown into the Tigris River, turning its waters black with ink. However, historical records suggest that rather than destroying all the knowledge, the Mongols seized and carefully studied many of these works.

Despite the enthusiasm with which Yahya ibn Barmak had translated Sanskrit texts into Arabic, such efforts dwindled in later generations—at least until the time of Al-Biruni, two centuries later.

Gradually, the influence of Ayurveda declined, and the Greek medical system of Galen (Unani medicine) gained prominence in the Islamic world. However, Arab scholars embraced the Indian numeral system, including the concept of zero and the place-value notation. This revolutionary approach to numbers soon transformed the field of mathematics globally. Through Fibonacci, these Indian numerals reached Europe by the early 13th century, shaping modern mathematics.

Thus, this is the remarkable journey of zero, a concept that originated in India and went on to reshape the world.

Source: Vayuveg

--

Bharati Web