Sinking Shafts for Pokhran-II Nuclear Tests: A First-Person Account

Pokhran II, finally, took place under Operation Shakti in 1998. A total of five tests with weapon grade plutonium were conducted – three on 11 May and two on 13 May. The tests included a 45-kiloton fusion bomb (also called hydrogen or thermonuclear bomb), a 15-kiloton fission bomb (atomic bomb) and three experimental sub-atomic devices of 0.5, 0.3 and 0.2 kiloton respectively.

Total Views |

India's first nuclear test was carried out on 18 May 1974 at Pokhran. The government termed it as a ‘peaceful nuclear explosion’, whereas it is more commonly referred to as Pokhran-I. After a hiatus of 7-8 years, a decision was taken by the Indira Gandhi government in 1981-82 to proceed with another set of nuclear tests, i.e., Pokhran-II. The army was asked to sink two deep shafts. The task was completed ahead of schedule but the tests were shelved due to external pressures. However, the shafts were kept duly maintained through regular dewatering and preventive oversight. The existence of deep shafts was kept a closely guarded secret.

Pokhran II, finally, took place under Operation Shakti in 1998. A total of five tests with weapon grade plutonium were conducted – three on 11 May and two on 13 May. The tests included a 45-kiloton fusion bomb (also called hydrogen or thermonuclear bomb), a 15-kiloton fission bomb (atomic bomb) and three experimental sub-atomic devices of 0.5, 0.3 and 0.2 kiloton respectively. The fusion and fission bombs were placed in the deep shafts sunk earlier. For sub-atomic tests, use was made of three abandoned dry wells in the near vicinity. These wells had earlier been dug by the villagers and deserted as no water had been struck.

This first-hand account recalls the sinking of the above-mentioned deep shafts.

During the period 1981-82, 113 Engineer Regiment was located at Jodhpur. The regiment had already made a name for itself for its indomitable spirit, fortitude and ingenuity. Therefore, its selection for Pokhran II came as no surprise. In fact, the assignment was seen as a validation of the high reputation that the regiment enjoyed in the Indian army.

It was an unprecedented assignment. To select sites and sink shafts hundreds of feet deep, with no experience and no equipment, was a huge challenge – more so as none of the officers had ever visited a mine or seen a shaft; nor had anyone studied mining engineering which is a specialised course.

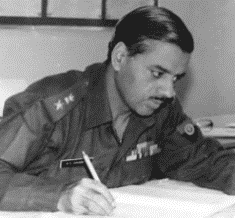

The regiment was being commanded by the late Lieutenant Colonel KC Dhingra (later rose to the rank of Major General). Colonel Dhingra was an extremely intelligent leader with phenomenal memory and exceptional capacity for diligent and sustained hard effort. I was a Major (Company Commander) in the regiment.

Lt Col KC Dhingra

It was the month of January 1981. The regiment was participating in an exercise in the Thar Desert when Colonel Dhingra was called to New Delhi for urgent consultations. After the termination of the exercise, while the rest of the regiment prepared to move back to Jodhpur, he asked me to accompany him for an operational reconnaissance to the border region. We set out in two jonga vehicles. He drove the first vehicle and I sat in the co-driver’s seat. The support staff was in the second vehicle.

En-route, he told me that the regiment had been tasked to sink a 12-feet diameter shaft of more than 500-feet depth. Repeatedly stressing the need for secrecy of the mission, he gave out other broad parameters. Both of us well understood the purpose of the shaft, yet the word nuclear or atom or test was never uttered. In fact, such taxonomy was never used by anyone during the entire task.

We knew it was a difficult assignment but did not comprehend the enormity of the challenge. We were civil engineers and knew little of shaft-sinking operations. A word about shaft-sinking will be in order here. To approach underground mineral seams, a vertical opening (shaft) is provided from the surface to the mining zone. These shafts are used to carry men, material and equipment to the mining zone; as also, to haul the extracted ore to the surface. Being the lifelines of all underground mines, shafts are sunk with exacting technical specifications and precision.

(Steel liners, ducts, pipes and electric fittings are visible)

Vertical shafts have to be absolutely plumb-perfect. Even a slight deviation is not acceptable. With water flowing along the walls, it is humid and hot. Normally, after 100 feet depth, temperature rises by one degree in every thirty feet. In the absence of fresh air, ventilation ducts are installed for pumping fresh air from top. Simultaneous operation of multiple rock drills produces unbearable din with clouds of dust hanging in the air. All diggers have to use ear plugs and wear protective eye-goggles.

As per the mining manuals, shaft-sinking is the most dangerous and hazardous task. It requires domain expertise and specialised equipment. There are a handful of shaft-sinking companies in the world, normally called ‘sinkers’. All mining companies outsource shaft-sinking operations to these ‘sinkers’. Our regiment had no experience, no knowledge and no equipment. Yet, our confidence in our ability to deliver never wavered. We knew that our self-belief, indomitable spirit, never-say-die approach and ingenuity would help us overcome all odds. As the saying goes – “Histories are scripted by the audacious.”

The task was to be carried out in the Pokhran ranges in the Thar Desert. Site selection was left to the regiment. With maps of the area in our hands, we traversed the ranges a number of times over the next two days to get a feel of its expanse. A nine square kilometres area was identified by us that was well away from the highways and the villages, thus satisfying our security and secrecy concerns.

Captains NPS Chauhan and DK Rajput

After our return to Jodhpur, Colonel Dhingra apprised the authorities at New Delhi about the general area selected. Once the go-ahead was received, I was asked to proceed to the Pokhran ranges to select the exact site for digging. Captains NPS Chauhan and DK Rajput accompanied me with a party of twenty jawans. We reached the ranges at sunset.

Unable to reach the pre-selected area, we decided to camp for the night in a flat area along the cart track Khetolai-Loharki. A 180-pound tent was quickly pitched for the three officers while the jawans slept in the 3-tonne vehicles.

Before going to bed, we were discussing the next day’s course of action in the dim light of the lantern when Captain Rajput shouted, “Snakes”. We looked down and were frightened to see tens of vipers and scorpions crawling all over the place. Apparently, we had intruded into their habitat. It was a sight that could send shivers down the spine of the bravest of the brave. Throughout the night, we did not venture to get down from our camp-cots, pressure on the bladders notwithstanding. The first thing that we did the next morning was to find an alternate camp site. However, little did we realise that vipers (called Russle’s Viper) were going to be an integral part of our lives during the entire duration of the task.

For site selection, we traversed the whole nine square km area a number of times but to no avail. We knew that the site had to be in the inter-dunal flat area with least sand over-burden and sufficient space for camping. We knew that Pokhran-I had suffered severe reverses due to underground water. Hence, our aim was to identify a location where sub-surface water would pose minimal impediment to shaft sinking operations. We understood the criticality of site selection, but had no knowledge or idea as to how to identify such a site.

We decided to meet the local inhabitants of Khetolai and Loharki villages to get the benefit of their ground knowledge. We told them that the army wanted to establish a permanent camp in the ranges and was looking for a site where water could be struck. They were very helpful and showed us numerous sites where they had attempted wells without striking water. They advised us to avoid those areas; and look for beri (Indian Jujube tree) and termite mounds as their presence generally indicates underground water.

At the end of the second day, we were no wiser as regards the selection of site. However, with no reptiles for company, we spent the night in peace. Next morning, we visited Jaisalmer and Pokhran towns to consult experts of the Central Ground Water Board and Rajasthan Ground Water Department. With the help of hydro-geological maps, they explained that the Pokhran ranges were a part of the lower Jurassic Lathi Formation, underlain by intrusive rocks at the basement consisting of granite, medium to coarse grained sandstone, shale and conglomerate.

As the main water bearing formations occur under unconfined to confined conditions in weathered/fractured zones, they could indicate presence of major aquifers trapped in impervious granite strata at depths of 1200 feet with reasonable certainty but not the perched aquifers at lesser depths. As we had to go down to 500 feet, the information was of little use.

We decided to approach Central Arid Zone Research Institute (CAZRI) at Jodhpur to seek their help in identifying water sources. They explained to us that the presence of perched aquifers (an underground layer of water-bearing permeable rock, rock fractures or unconsolidated materials) and underground streams depended on the geology and geomorphology of the area. Most disappointingly, they also underlined the impossibility of predicting perched aquifers and underground streams. CAZRI readily gave us geologic and topographic maps of the area. We studied them in detail but no tangible inferences could be drawn. We needed application of a more exact and scientific method. The challenge of selecting an exact spot for digging was proving overwhelming.

As pressure from New Delhi was building up, Colonel Dhingra asked us to revisit Pokhran ranges to expedite site selection. I was soon back in the Pokhran area with a team of officers and men for further ground reconnaissance. After much scouting and ground survey and the inputs acquired from different agencies, four sites (A, B, C and D) were tentatively shortlisted, with their inter-se distance varying between 900 to 1400 meters. All the sites were in hard crusted inter-dunal flats (with least sand over-burden) with sufficient space for erecting rigs and other infra-structure. Close proximity of sand dunes was considered essential for concealing disposal of dug earth, lest prying satellites detect our activities.

We contacted the local villagers once again to obtain their views regarding the possibility of striking a reliable water-source at the four shortlisted sites for establishing an army camp. We, of course, intended to eliminate those sites. The well-meaning village elders advised us to seek the help of local water-diviners. Water-divining or dowsing is an esoteric ancient method in which the locals have immense faith. It is an intuitive practice of using a divining rod to find sub-terrarium water. It is believed that the flow of underground water induces some vital currents above the surface and a person with induction attributes can sense them through the movement of a freshly plucked twig.

The practice of dowsing is also based on the conviction that perturbations on the earth's magnetic field may coincide with the existence of groundwater. A dowser’s body serves as an electrical conductor and when it moves through the earth's magnetic field, small electric potentials are generated. It is said that Moses searched for water in the Sinai desert using his divining rod around 1250 BC.

Most dowsers use forked sticks while others use two sticks. Some use steel rods bent into L-shape. They are held in hands loosely so that even a slight hand motion (influenced by magnetic field perturbations) becomes sufficiently noticeable. However, as their approach is solely sensory, the dowsers can neither guarantee the presence of water (including depth and quantity) nor its absence. We found the idea interesting but brushed it aside as being non-scientific.

Much to our surprise, the local headman of Khetolai village brought a dowser from Pokhran town to our camp location the next evening. As we did not want to hurt the feelings of the well-meaning headman, the dowser was allowed to commence appraisal of the four sites shortlisted by us.

Dowser’s Sensors: Freshly Plucked Forked Twig or Twin Sticks

It was a full moon night. The dowser took out a freshly plucked forked twig of local beri tree from his bag and washed it with water with a short incantation. He was accompanied by his mate with a lit lamp, placed in a brass tray, duly bedecked with flowers. With the flickering flame of the lamp casting eerie shadows on the sand-dunes, it was a surreal experience for all of us.

Nonetheless, we were relieved to hear the dowser declare all the four sites unfit for water prospecting. Even though it was a gratuitous input without any scientific authentication, we certainly felt upbeat. It sounds incongruous that a dowser’s testimony also played a part in helping determine the site for a nuclear test! Indeed, a weird proposition.

During Pokhran-I (January 1974), ingress of water had stalled the progress within three months of commencing digging. The incomplete shaft had to be discarded and a dry abandoned well was prepared for the test. For our proposed test (Pokhran-II), a 500 feet deep shaft was essential. No abandoned well could have met that requirement as they rarely exceed 120 feet depth. To cater for unforeseen contingencies, the authorities decided to attempt digging at two sites simultaneously. Consequently, we had to select two out of the four shortlisted sites. We did much brain-storming but doubts continued to linger.

Although wary of compromising secrecy, Colonel Dhingra agreed to seek help of a local hydrogeology agency that specialised in water prospecting for wells. The agency was told the same story i.e., the army was looking for a camp site with a water source. The agency could carry out core drilling for geologic sampling up to 150 feet only. Core drilling helps in extracting a cylinder of material, akin to the functioning of hole-saw. The removed core (in cylindrical form) is laid on ground, logged and studied. In our case, the core logging declared all the sites ‘unfit for sinking well’, meaning thereby that water was not available in exploitable quantity up to 150 feet depth. Though encouraging, the reports were not a clincher as we had to go down to more than 500 feet.

As a last resort, we obtained the services of a government agency to employ geophysical method of detecting underground aquifers. The method is based on the capacity of the soil or rock to conduct electricity and the measurement of its conductivity. A direct current is sent down into the earth at the selected spot and electrodes placed in different arrays record the measurements. Deductions are drawn about the depth, size and quality of water bodies. As the efficacy of the equipment employed precluded any substantive result beyond 200 feet depth, their results were also not conclusive.

A number of meetings were held by Colonel Dhingra to collate and analyse all the inputs received. Painstakingly, comparative site appraisals were carried out. Sites A and C emerged as the preferred sites. It must be admitted that hunch and the proverbial sixth sense also played a considerable role in the final selection. Thereafter, Colonel Dhingra and I proceeded to Pokhran for confirmatory ground reconnaissance. Maps had to be annotated to convey the grid references to New Delhi.

By the time we reached Site A, the sun was already going down. The centre point of the proposed shaft was duly fixed on ground. I requested Colonel Dhingra to do the honours of driving an iron picket as the marker. A soldier held the iron picket on the spot and Colonel Dhingra was given the sledge hammer. He stepped forward while the rest of us formed a circle around him.

It was a momentous occasion. With the setting sun’s rays lighting up sand dunes in different hues of golden colour, it was an idyllic experience. The tranquillity of the desolate desert added peculiar solemnity to the surroundings. Colonel Dhingra faced the sun, closed his eyes for a minute and perhaps, sought heavenly blessings. Significance of the occasion had overwhelmed us all and we were standing as if in a trance, which was broken only by the thud of the hammer blow.

As it was getting dark, we rushed to Site C which was 900 meters away. The same procedure was repeated except that Colonel Dhingra asked me to drive the picket. It was a gracious gesture.

During our long drive back to Jodhpur, we hardly exchanged any notes. The die had been cast. Future of India’s nuclear ambitions depended on our site selection. The thought weighed heavily on us.